Why Trump's tariff won't revive American industry

Yet his (and Elon Musk's) efforts to gut state capacity and reverse Biden's industrial policies will only ensure America falls further behind.

Tariffs have become the defining pillar of Trump’s economic policy. His justifications are often convoluted, if not outright absurd—such as claiming tariffs on Mexico and Canada would protect America from the "major threat of illegal aliens and deadly drugs."1 Yet beneath the bluster, Trump and his advisors see tariffs as a means to shield domestic industries from global competition and to revive American manufacturing. These economic nationalist policies mark a departure from decades of U.S. trade orthodoxy, but it is far from unprecedented.

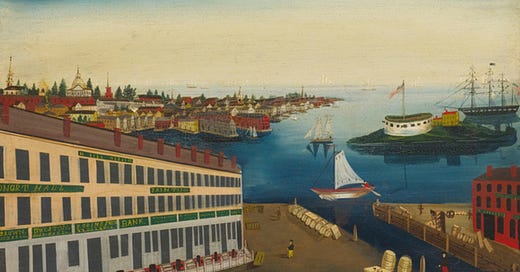

While the U.S. has long championed free trade, its earlier history tells a different story. Before embracing free markets, it was one of the most aggressive users of protectionist policies and the intellectual birthplace of modern economic protectionism. In the 18th century, Alexander Hamilton laid the foundation for this approach, and throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries, tariffs became a cornerstone of U.S. economic policy—maintaining some of the highest average tariff rates on manufactured imports in the world between 1861 and 1933.2

(Relatedly, see my article on America's Era of Hidden Industrial Policy)

However, just because tariffs worked in the past doesn’t mean they will be effective today. For them to succeed, there must be strong domestic competition or targeted policies that actively push firms to improve productivity rather than rely on protection alone. U.S. tariffs worked in the 19th and early 20th centuries because they effectively spurred domestic competition. American labor costs were low, and industrial goods were relatively simple, with few technological barriers to entry. This made it easier for domestic firms to establish themselves, compete, and eventually grow into competitive exporters—for which the bar was not high since U.S. firms only needed to catch up to British competitors.

Today, the U.S. has a vastly different political economy. Labor costs are among the highest in the world. At the same time, industrial production has become increasingly complex, demanding cutting-edge technology, specialized skills, and economies of scale. Global competition is also fiercer than ever. Where American firms had previously only needed to surpass their British counterparts, they must now compete against numerous other countries (many with much lower labor costs) in manufacturing. These conditions make it far more challenging for domestic firms to succeed without targeted state support.

As a result, slapping tariffs on imports will not generate the growth-inducing response they did in the 19th century. Absent domestic competition or targeted industrial policies, the cost of tariffs will simply be passed onto the American consumer. Instead, effective state intervention must go beyond blocking foreign competition to active, strategic policies that accelerate firm competitiveness. This means intervening at the firm and sector level, coordinating supply chains, ensuring a steady pipeline of skilled labor, and providing targeted financing to help firms scale and compete internationally.

Lessons from East Asia

The East Asian developmental states make for good historical case studies. In the 1960s and 1970s, countries like South Korea and Taiwan actively protected their domestic industries with tariffs. But unlike the U.S. today, they did not stop there. Their governments also played an active role in shaping industrial development, ensuring that firms receiving state support were actually working toward higher productivity, technological advancement, and global competitiveness. As a result, by the 1980s, both countries had achieved miracle-level economic growth, transforming from low-income nations into formidable global competitors in advanced manufacturing.

What made their industrial policies so effective? A key factor was investment coordination, where the state actively reduced uncertainty for firms by ensuring that complementary investments across supply chains were made in tandem. This prevented firms from hesitating to invest due to gaps in upstream or downstream industries. Rather than letting market forces randomly dictate industrial development, the state played a hands-on role in aligning production and investment decisions, creating a stable and predictable environment for industrial growth.

South Korea and Taiwan also implemented targeted subsidies with strict conditionality. This meant that firms only received state support if they met pre-defined targets—particularly in export performance. This conditionality forced firms to boost their productivity and eventually compete internationally rather than depend on continuous government support. Economist Alice Amsden, one of the first to study South Korea’s industrial development, described this process as the "disciplining" of capital—a process where subsidies were not mere handouts but tools to drive industrial upgrading.

(Relatedly, I've written about how China fares when it comes to disciplining capital here.)

This combination of protectionism plus strategic state intervention allowed South Korea and Taiwan to go from low-cost manufacturers to leaders in industries like semiconductors, shipbuilding, and consumer electronics. It's worth emphasizing here that this type of state intervention (e.g., coordinating investment and subsidies with conditionality) required robust organizational resources within the state itself—not just the fiscal capacity to subsidize firms but also an effective and highly capable bureaucratic apparatus. For instance, the ability to discipline capital requires a bureaucracy capable of data collection, auditing firms, and enforcing consequences, preventing inefficiency and rent-seeking. As a result, East Asia's success was not simply a matter of having the right state interventions in place but having the state capacity to manage, coordinate, and monitor the process of industrialization.

Dismantling state capacity

If history teaches us anything, it’s that tariffs alone are not enough to rebuild American manufacturing. Protectionism can play a role, but only when paired with proactive industrial policy—a lesson that the East Asian developmental states understood well.

This approach is not entirely foreign to the U.S. The CHIPS and Science Act and the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) passed under the Biden administration share many of the same characteristics that allowed the East Asian model to succeed. These policies provided targeted support for strategic industries, incentivizing domestic semiconductor production, clean energy innovation, and high-tech manufacturing.3

However, rather than building on these initial efforts, Trump is actively working to reverse them. He has already attempted to suspend all IRA funding disbursements. With the help of Elon Musk who heads the newly formed Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE), he also intends to dismantle the federal bureaucracy, which would eliminate the state capacity required for disciplining firms and coordinating investments.

At best, Trump's tariffs amount to little more than political theater—a performance of economic nationalism rather than a serious plan for industrial revival. At worst, they are a tax policy in disguise—a way to generate government revenue to pay for tax cuts. Without coherent industrial policies and the state's capacity to enforce them, these tariffs will do far more harm than good to the American economy—driving up consumer prices while doing nothing to rebuild America’s manufacturing base.

Source: https://www.cnn.com/2025/02/01/politics/mexico-canada-china-tariffs-trump/index.html

These tariffs were a major point of contention between the North and the South. The industrializing North favored high tariffs to protect its emerging industries, while the agrarian South, which relied on exporting raw materials like cotton and importing cheaper manufactured goods from Europe, saw tariffs as an economic burden that raised the cost of imports and invited retaliatory trade measures.

However, it was unclear whether the subsidies provided under the IRA and the CHIPS and Science Act were designed with the necessary conditionalities and backed with enough state capacity to ensure industrial competitiveness. For instance, there are no clear measures to guarantee that the nearly $8 billion awarded to Intel under the CHIPS and Science Act will be productively invested rather than a corporate giveaway. But under a Trump administration intent on gutting state capacity, the risk of these policies failing is even greater.

You nailed it: "Absent domestic competition or targeted industrial policies, the cost of tariffs will simply be passed onto the American consumer."

Thank you for this insightful piece!

Yes! This is correct, tariffs must be part of a broader paradigm set, in fact, they always will be whether you want them to or not as they will always effect and be effected by the elements of the broader policy space; and the sets design, execution and intents can have immense impact on the results.

I wrote this to someone the other day on the same theme: The USA's Old Republic used tariffs as a part of a broader policy and complementary tool set within a politically, economically, governmentally, and scientifically decentralized system. The policy paradigm was designed to generate a diffused and redundant economy for purposes extending far beyond immediate job creation. They helped generate diversified and redundant scientific and engineering ecosystems, variegated academic ecosystems, and deep, layered supporting industries that made other forms of development (such as various types of construction) far easier and more capable. And all those things would in turn be complementary and inter supporting (sometimes in amazing innovation ways no one had thought of!) This, in turn, generated other soft but and important things like widespread and diversified arts and cultural growth

But the USA's Old Republic did not rely solely on external trade protectionism to achieve these outcomes. It also maintained internal inter-regional trade frictions, albeit to a lesser extent, and, critically, it had substantial interregional capital flow inhibitors. And its unfortunately not well known now, but for the first 200 years of its existence, the USA maintained internal capital control mechanisms that, while preserving a deep national capital market, making it so that access to capital and decision-making about its deployment were geographically, sectorally, and societally diffused. This structure prevented financial and industrial centralization, allowing local and regional economies to develop according to their own conditions and with a limited but still substantial local economic, cultural, and scientific agency instead if just being dictated by national or global financial power centers.

All of these policies functioned as part of a coherent set, reinforcing one another within a decentralized political system. This system’s governmental-policy decision making architecture was dominated by two decentralized and publicly accessible mass-member parties that represented a broad spectrum of interests and made it so that economic decision-making was not captured by a single elite group. Because the system was decentralized, it could effectively manage the balance between protectionism, internal friction, and capital diffusion, making it so that industry and finance did not become overly concentrated in any single region or sector, while generating a deliberately redundant, heterogenous, pluralistic, and vibrant economy that was the best the world has ever known!