Last week, I published a primer on China’s cloud sector on ChinaTalk, outlining the key reasons why it lags behind its U.S. counterpart. This piece is the deep dive version.

Much of the current discourse on China’s cloud industry is framed through the lens of geopolitics—and for good reason. Cloud infrastructure forms the computational foundation on which modern AI systems are built. If the past decade of U.S.-China relations was defined by a “chip war,” the coming decade may well be shaped by a “cloud war”—a shift that Kevin Xu of Interconnected has long written about.

Yet, missing from the discourse is a clear assessment of China’s indigenous capabilities in cloud computing. Long before the relationship between these two countries soured, the development of the cloud in both the United States and China was well underway. And even then, U.S.-based cloud firms established a clear lead.

Given how few players there are in the cloud sector, it may seem like the United States' lead is about firm competency—that the decisions of individual firms have an outsized impact on their competitiveness. While firm-level choices are certainly important, a broader comparison between the U.S. and Chinese cloud industries reveals that national-level factors play a critical role as well. They help explain not just why China lags behind, but how its cloud industry diverges fundamentally from that of the United States—not merely in degree, but in kind. Such a comparison sheds light on China’s unique strengths and structural dependencies, as well as the broader political-economic forces that shape—and at times constrain—its cloud ambitions

China’s cloud lags the U.S.’s

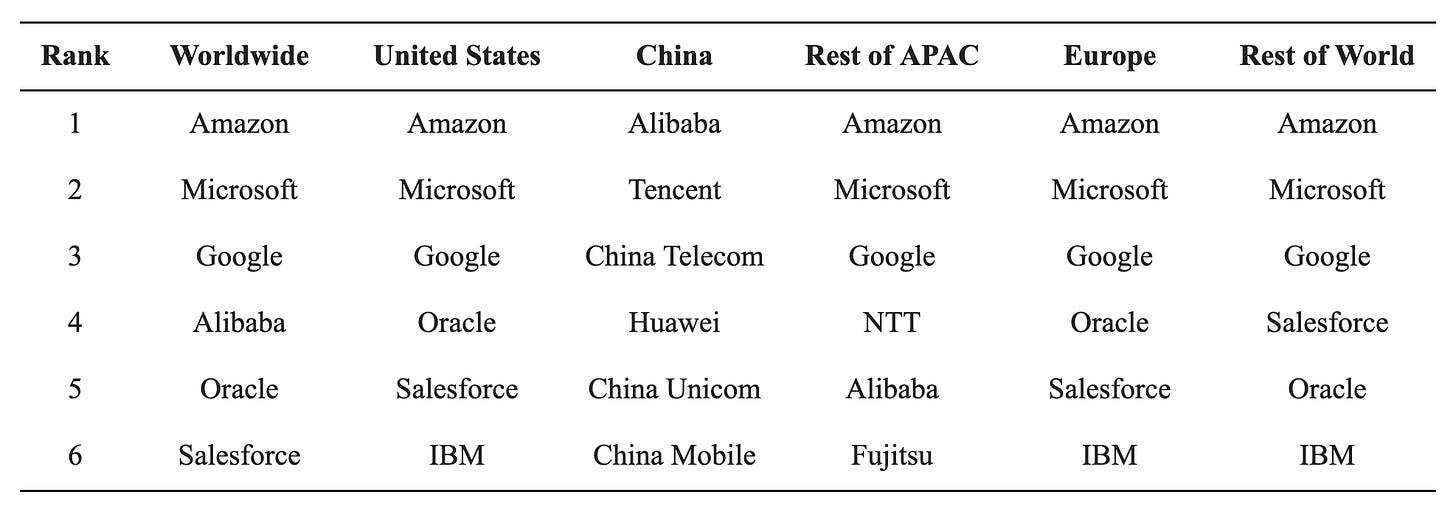

To assess the political economy of China’s cloud computing sector, we must first understand the global competitive landscape. The cloud industry in the United States is dominated by three major players: Amazon Web Services (AWS), Microsoft Azure, and Google Cloud. While other firms like IBM and Oracle also operate in the sector, these three giants have increasingly pulled away from the rest of the pack, consolidating their leadership. And more recently, the rise of generative AI has catalyzed a new cohort of specialized cloud providers such as CoreWeave and Lambda, which focus on compute-intensive AI workloads.

China’s cloud industry is far behind but follows a somewhat similar pattern, with the country's biggest tech players, Alibaba and Tencent, leading the market. Their prominence is unsurprising given their backgrounds as digital platform firms. However, a crucial distinction between two cloud industries lies in the role of telecom infrastructure firms.

Unlike in the United States, where no telecom provider has successfully entered the cloud sector—AT&T made an attempt but ultimately exited after selling its assets to IBM—China’s cloud landscape is also composed of firms that have long specialized in telecommunications infrastructure. Huawei, originally known for its dominance in 5G and telecom equipment manufacturing, has aggressively moved into the cloud business and is now among China’s largest cloud providers. Meanwhile, China’s three state-owned telecom giants—China Mobile, China Telecom, and China Unicom—have also made significant investments in cloud computing, leveraging their extensive network infrastructure to expand into this space.

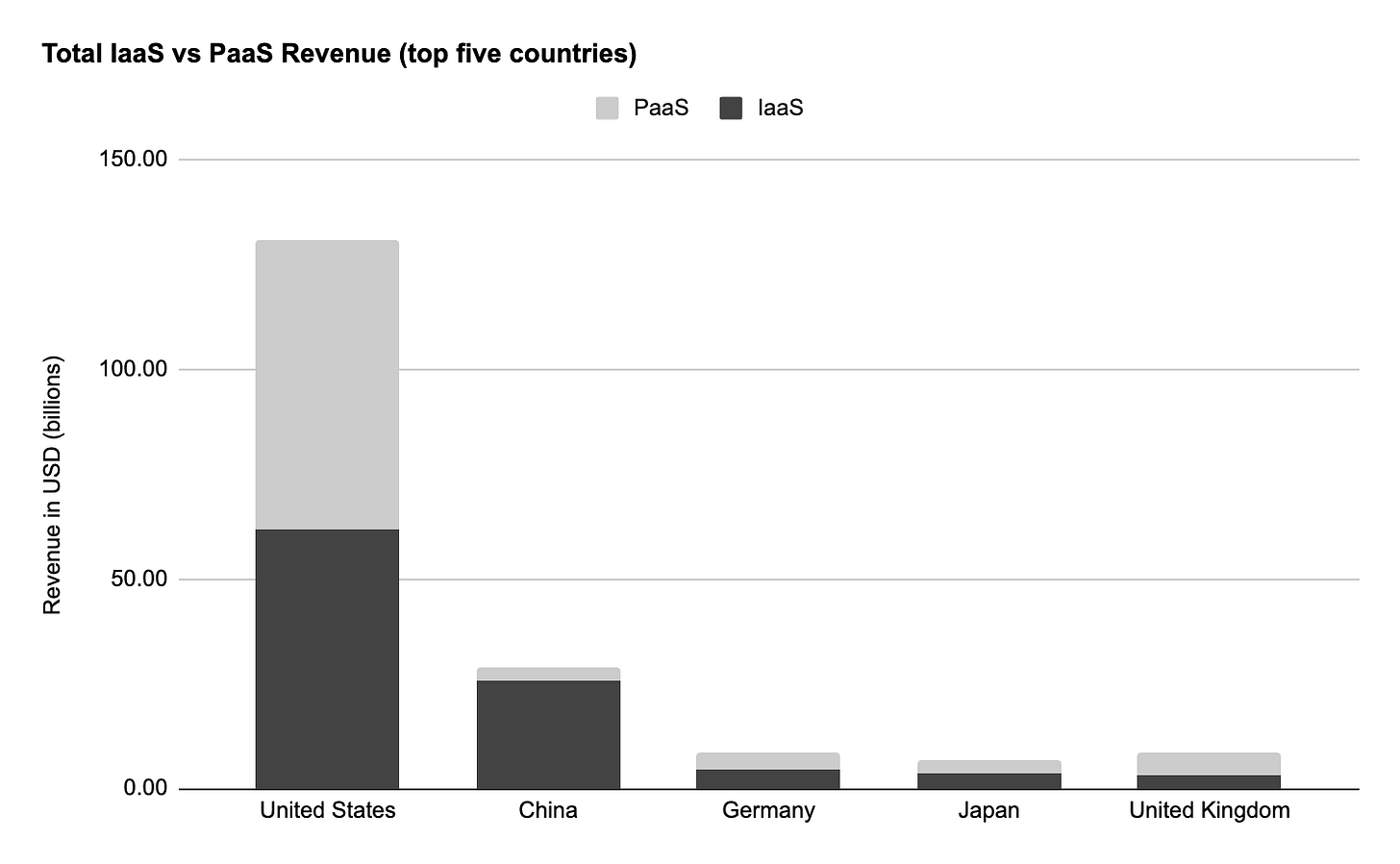

A key indicator of the competitive gap between U.S.- and Chinese-based cloud firms is revenue. By this measure, U.S. companies dominate by a wide margin, with AWS alone generating more revenue than the entire Chinese cloud sector combined.

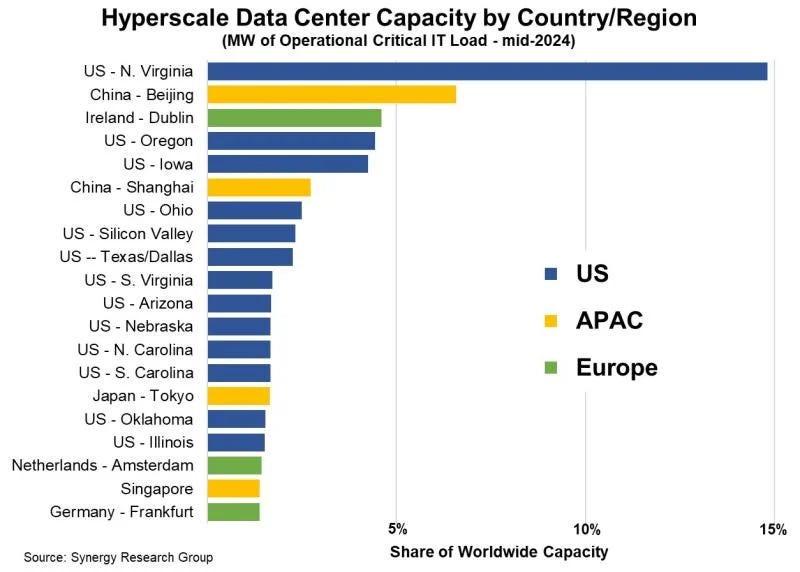

In terms of the number of data centers built out, the United States has also far outpaced the rest of the world, including China. The former accounts for 51% of the world's data center capacity while the latter only sits at 16% as of mid-2024.

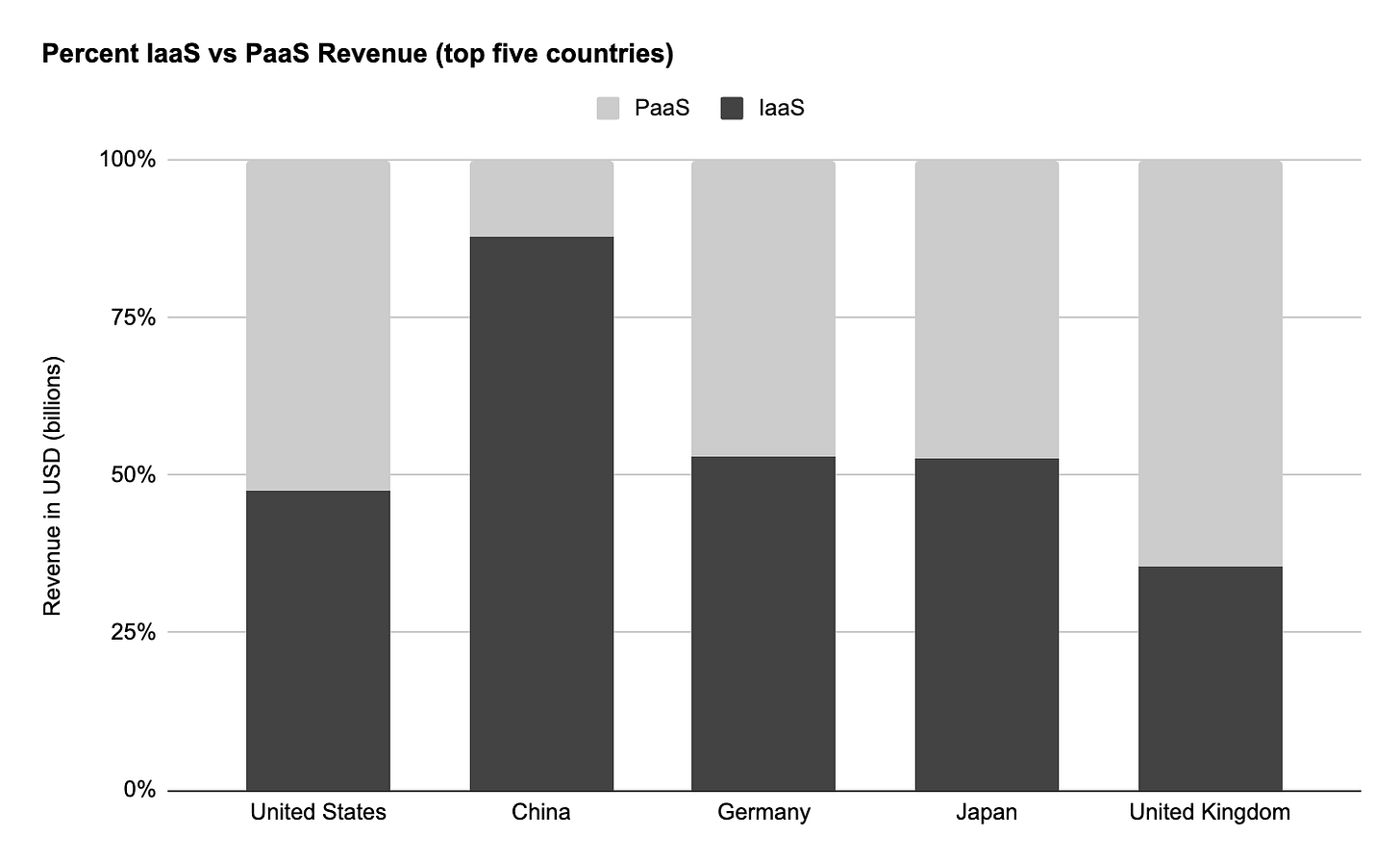

However, revenue alone does not fully capture the structural differences between the two industries. A deeper distinction emerges when we break down revenue by cloud service type, specifically Infrastructure-as-a-Service (IaaS) versus Platform-as-a-Service (PaaS)—the two prongs of cloud services.1

IaaS consists of the basic building blocks of computing—compute, storage, and networking—delivered as virtualized infrastructure. This means that users can provision and manage them using code without buying any physical IT infrastructure, allowing clients to save on expensive upfront capex costs. Because these three components are the basic building blocks for any IT infrastructure, it is relatively easy for businesses to migrate to using IaaS with minimal changes.

PaaS, by contrast, requires deeper integration on the part of the customer. It is primarily targeted at software engineers so that they can deploy application-level code without having to worry about the underlying infrastructure. From the perspective of cloud providers, PaaS is far more lucrative, generating higher margins than IaaS.

While both U.S.- and Chinese-based cloud firms derive the majority of their revenue from IaaS, U.S. firms generate a significantly larger share of revenue from PaaS. Of the top five countries by cloud revenue, China, in fact, stands out by its disproportionate IaaS revenue. This difference is crucial. What it means is that Chinese cloud providers, despite their size, have not been able to move up the cloud value chain to capture higher margin activities. This means that their customers are treating the cloud more as a commodity rather than a platform to transform business operations and enhance productivity.

Another key measure of competitiveness is global reach. This will give us a sense of what the potential addressable market is for U.S.- versus Chinese-based cloud firms. Here, the divide between the two countries is even more pronounced. U.S.-based cloud services are used worldwide, with AWS, Microsoft Azure, and Google Cloud enjoying dominant market positions across North America, Europe, Latin America, and parts of Asia. In contrast, Chinese cloud providers remain largely confined to their domestic market. Alibaba Cloud has made some inroads into Southeast Asia, but even there, its presence remains marginal compared to its U.S.-based counterparts. This pattern mirrors the broader trend in consumer digital platforms, where Chinese tech giants like Alibaba, Tencent, and ByteDance have built dominant domestic ecosystems but have struggled to expand to international markets.

Divergence in diffusion

New technologies are introduced through one of two processes: creative destruction or creative accumulation. In the first, disruptive challengers introduce innovations that upend existing industries, displacing incumbents in the process. This model, famously described by Joseph Schumpeter, characterizes moments of radical technological transformation, where new entrants—often startups or firms from adjacent industries—leverage technological breakthroughs to dethrone established players.

In contrast, creative accumulation—also an observation captured by Schumpeter but in his later work—occurs when innovation is driven by existing incumbents who build upon their technological and market advantages rather than being displaced by newcomers. In these cases, innovations tend to be resource-intensive and require significant firm capacity, making it difficult for small firms to participate in the innovation process.

What kind of innovation the cloud is is important. Where the rise of the platform economy—with digital platforms like Google and Amazon displacing traditional giants in media and e-commerce—was an example of creative destruction, the cloud computing sector emerged from the incumbents of the tech sector. These incumbents have specific characteristics that make entering the cloud business possible. For instance, they are massively cash-rich, allowing them to make long-term low-margin investments in data centers, and have deep technical capacity—both of which come as a result of their domination in the platform era.

However, it was not inevitable that the United States would become the undisputed leader in cloud computing. China had comparable technology incumbents that could have spearheaded their own cloud industry. In fact, Huawei established its cloud division in 2005—a year before AWS launched its first cloud services. Alibaba also had a monopoly position in e-commerce when it entered the cloud market in 2009. Like their U.S.-based counterparts, both companies were financially powerful and technologically sophisticated, well-positioned to ignite a parallel cloud revolution in China.

Yet, as I have shown, China has not come close to rivaling the United States in cloud services. Despite its early start, Huawei’s cloud business was stagnant for over a decade and only began receiving more resources in the late 2010's. Alibaba and Tencent have been gaining ground and are viable competitors but still trail far behind U.S.-based firms. And on top of that, China not only lags in overall cloud revenue but is also disproportionately reliant on low-margin IaaS rather than higher-margin PaaS.

This divergence is a good reminder that the diffusion of technology is neither uniform nor inevitable. Nor is it simply a matter of firm decisions. The same fundamental technologies can be adopted in different ways depending on the national context in which they are deployed. And as I'll argue next, national-level factors within each of these two countries have produced decisive outcomes in the cloud sector on both the supply- and demand-side.

Demand-side limitations

The biggest challenge facing China’s cloud firms lies on the demand side. A 2014 McKinsey Global Institute report found that Chinese businesses spent, on average, just 2% of their revenue on IT—half the global average.2 Historically, Chinese businesses have been reluctant to invest in IT infrastructure due to its high costs and uncertain returns on productivity. In theory, IT spending—whether on enterprise software, upgraded infrastructure, or cloud services—is intended to drive efficiency and long-term productivity gains. But such gains aren’t immediate or guaranteed; they depend on workforce training, the standardization of business processes, and the ability to effectively integrate new technologies.

Moreover, advanced IT investment is only worthwhile if firms have structured data, formalized operations, and codified knowledge and workflows—conditions that are often lacking in industries reliant on informal or ad hoc processes. This makes IT spending a risky proposition for many firms, particularly in countries where cutting labor costs or intensifying worker exploitation offers a faster and more predictable way to improve margins.

Many Chinese firms are a case of this. The country's limited IT spending is a consequence of low labor costs and weak labor protections, which diminish the incentive for businesses to spend on IT solutions. Where labor is cheap and employment regulations favor flexibility, firms can scale operations by relying on human workers rather than automation or advanced IT systems.

Another major hurdle for adopting the cloud is that Chinese businesses tend to have informal and non-codified work processes. Unlike in the United States, where standardized workflows make it easier to integrate software solutions for automation and efficiency, many Chinese companies operate with highly customized or ad-hoc procedures that are difficult to codify into software. Decision-making can often be relationship-driven rather than process-driven, and informal workarounds frequently replace structured workflows.

And as a result, many Chinese businesses use cloud computing only for basic, low-cost functions—such as maintaining an online presence—rather than leveraging it for its productivity-enhancing capabilities. These dynamics are particularly salient for low-wage labor-intensive sectors, which dominate China’s economy; for firms in such sectors, it is cheaper to hire additional workers than it is to upgrade their IT systems for non-guaranteed gains in productivity.

These problems are reflected in the industrial composition of China versus the United States. In the United States (and in Europe too), cloud adoption has been driven by industries with high IT budgets, such as banking and securities, where firms allocate an average of 7.88% of their revenue to IT. Sectors like insurance and business services, which typically spend 4-5%, are also common. These industries form a significant share of the economy and are key drivers of enterprise cloud demand. By contrast, China’s economy is dominated by low-IT-spending sectors such as manufacturing, which accounted for 38.3% of GDP in 2023 but allocates only 2-2.3% of revenue to IT, and construction, which represents 6.8% of GDP with an even lower 1.68% IT budget.

Supply-side limitations

When it comes to the supply-side, Chinese cloud firms appear to have comparable advantages to their U.S.-based counterparts. Alibaba rose alongside Amazon in the 2000s and early 2010s, establishing itself as a dominant force in e-commerce with an expanding ecosystem of digital services and highly competent technical workforce. In terms of financial resources, Alibaba and Amazon were also comparable. In 2010, Alibaba had $2.5 billion in cash on hand, while Amazon had $8.7 billion. By 2020, those figures had grown to $54 billion and $84 billion, respectively. Amazon only pulled far ahead in the 2020s, well after their dominance in the cloud was established.

These figures suggest that Alibaba also had the requisite capital to invest in data centers during the critical years of the sector’s growth. In some respects, one might even expect China to have something of an advantage. AI analysts like Grace Shao have pointed to China’s strengths in energy infrastructure, a key input in operating data centers. Still, China’s cloud sector has lagged in both scale and profitability.

Part of the reason is because China's cloud firms are missing two critical ingredients. First is China's relatively weak enterprise software ecosystem. Because cloud revenue ultimately comes from other businesses, enterprise software is critical as it acts as a stepping stone for customers to adopt the cloud. Take Apache Spark, an analytics engine for big data and machine learning. While Spark itself is open-sourced and thus free to use, its widespread enterprise adoption in the United States has been driven by companies like Databricks, which help customers adopt the technology and even provide a "managed" version of the open-source software. For customers that use Spark, moving to the cloud becomes a no-brainer, especially because Databricks has deep partnerships with Microsoft Azure and Amazon Web Services that make the transition to using Spark in the cloud seamless.

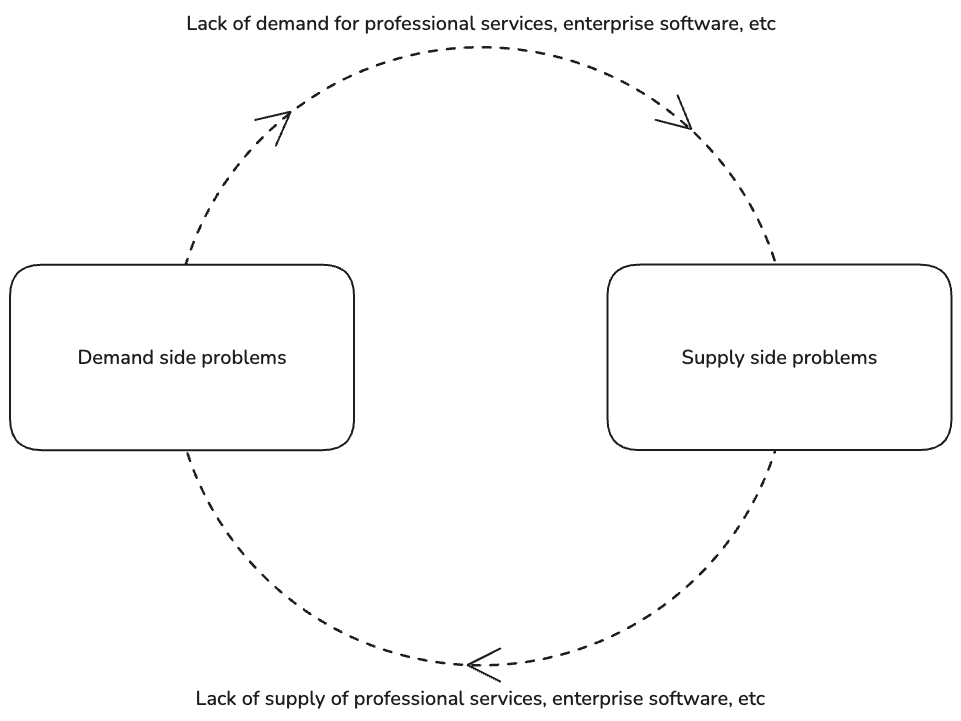

In the United States, firms like Databricks are everywhere. And U.S.-based cloud providers have taken advantage of this mature software ecosystem to attract more customers to the cloud. China's software ecosystem, by contrast, remains underdeveloped. As a result, Chinese firms not only have fewer incentives to migrate to the cloud but, when they do, they are more likely to use it for basic, low-margin IaaS rather than the higher-margin PaaS offerings.

Second, China lacks a mature ecosystem of professional IT service providers, which are crucial for helping businesses transition to the cloud. Cloud migration is a complex process, and different industries face unique challenges in adapting their IT systems. In the United States, a vast network of professional consulting firms—such as Accenture and Deloitte—play a key role in guiding enterprises through this transition. These firms not only act as intermediaries between cloud providers and enterprise clients, but also bring with them deep industry-specific expertise and technical knowledge, allowing them to tailor cloud solutions to the needs of different sectors. Critically, when cloud providers partner with these consulting firms, they also gain access to their portfolio of clients, which lowers customer acquisition costs and accelerates enterprise adoption. In China, however, such professional services hardly exists, leaving potential clients with fewer resources to navigate the complexities of cloud migration.

The lack of professional IT services and an enterprise software ecosystem in China does not just slow cloud adoption—it also reinforces the very conditions that make these services scarce in the first place. Because businesses are not widely adopting cloud-based enterprise solutions, there is little incentive for firms to develop and invest in professional IT services or enterprise software, which, in turn, reinforces the initial demand-side problem. This creates a vicious cycle in which supply-side constraints suppress demand and vice-versa, leaving China’s cloud ecosystem stuck in a suboptimal equilibria state.

State coordination

While China’s cloud growth has been held back by these demand- and supply-side constraints, state intervention has, to some extent, helped offset these structural limitations.

As early as 2011, the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC), the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (MIIT), and the Ministry of Finance allocated $236 million to strengthen domestic cloud providers, channeling subsidies to firms like Alibaba, Tencent, and Baidu to expand their cloud services. By 2018, Chinese state planners deepened their commitment, securing an agreement with the China Development Bank to invest $15 billion in cloud computing, smart cities, and big data technologies.

The most ambitious and far-reaching cloud-focused industrial policy came in 2020 with the launch of “Eastern Data, Western Computing.” Designed to expand data center infrastructure in China’s energy-rich western provinces, the policy aims to ease the strain on resource-constrained eastern cities like Beijing, Shanghai, and Shenzhen, where the bulk of the country’s users live. At this point, it is impossible to discuss the political economy of China’s cloud sector without also talking about this initiative. In just its first two years, the government has already invested $6.1 billion in data center construction, underscoring the scale of state involvement in shaping China’s cloud infrastructure.

As demand for energy-intensive workloads—such as AI model training—continues to grow, coordinating energy and cloud infrastructure has become increasingly critical. AI model training requires massive computational power, can take days or even weeks, and is extremely costly in terms of energy. However, once trained, a model is ready for deployment and real-time use—a process that requires far less computation but demands low latency for seamless performance. The East Data, West Computing initiative is designed to address this challenge by relocating energy-intensive tasks to resource-rich regions in western China, where land, energy, and cooling are more plentiful and cost-effective. This leaves latency-sensitive tasks—such as AI inferencing, which generates real-time predictions and is far less energy-intensive than training—to be processed in eastern coastal cities, where proximity to end users helps minimize lag.

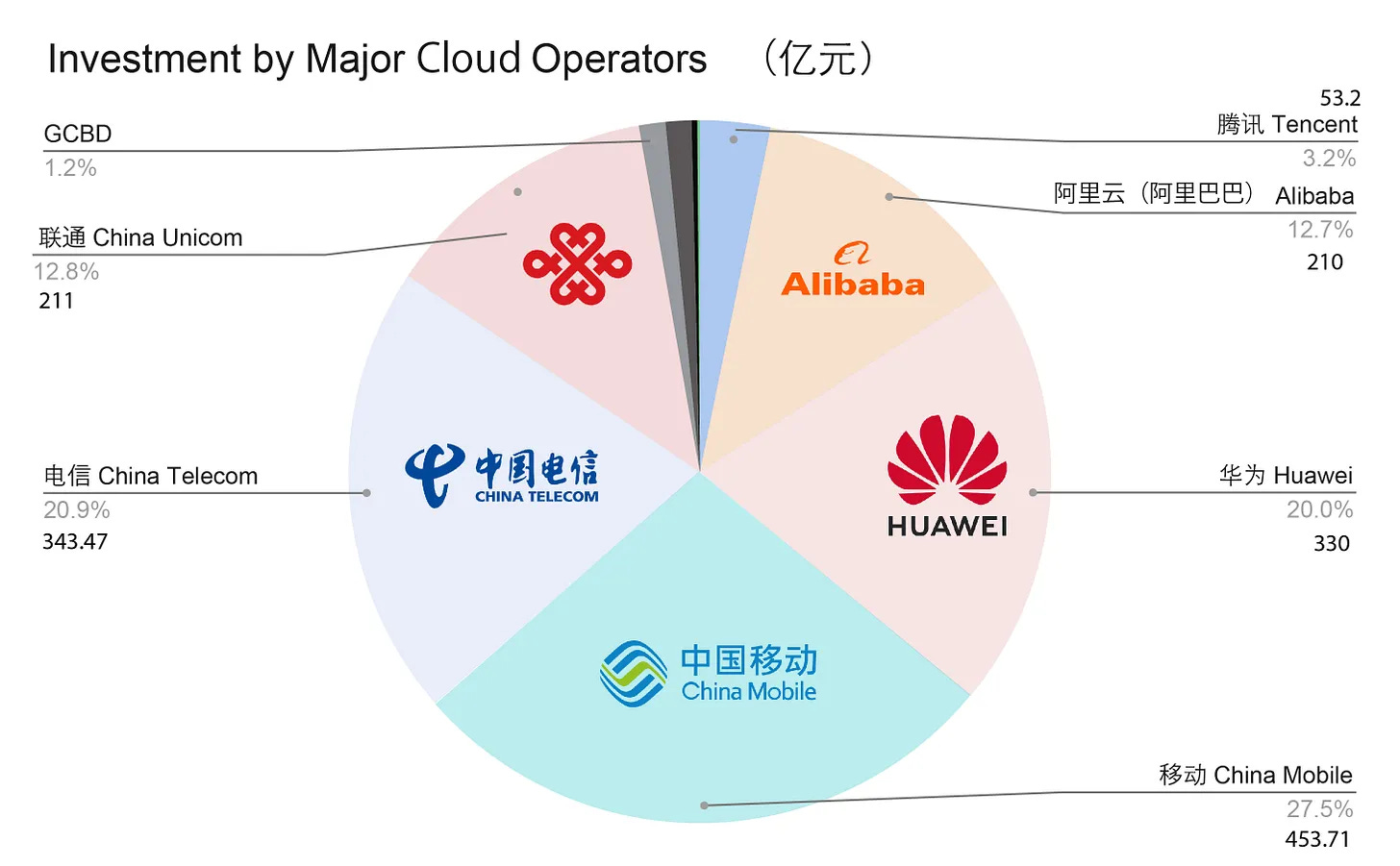

A national scale effort to coordinate cloud infrastructure with the country's energy capacity is no small task. To a large extent, what makes this coordination possible is the fact that China’s cloud ecosystem isn’t comprised solely of publicly traded private firms. China's cloud sector also features privately held firms like Huawei and state-owned enterprises (SOEs) such as China Telecom, China Mobile, and China Unicom.

Different ownership structures shape a firm’s ability to raise and allocate capital, influencing long-term investment decisions. For instance, publicly traded firms operate under stringent shareholder expectations that forces them to prioritize short-term profitability. However, being cash-rich—as firms like Amazon and Alibaba are—have eased shareholder pressure, allowing them to sustain massive investments in cloud infrastructure despite its low margins and long payoff periods.

Lacking this financial buffer, firms must leverage alternative ownership structures to secure the patient financing required for building cloud infrastructure. Being privately held, as is the case of Huawei, allows firms to prioritize long-term strategic objectives, including those aligned with national industrial policy, without the constant need to satisfy external investors. SOEs such as China Telecom and China Mobile are similarly shielded from shareholder scrutiny, giving them the ability to allocate resources based on state-directed priorities rather than market-driven returns. China Telecom was in fact recently designated as the country’s first official national cloud provider, cementing its role as the preferred cloud service provider for government projects.

Unsurprisingly, these telecom SOEs play a leading role in the Eastern Data, Western Computing initiative. According to research from Sinocities (see graph below), the SOEs are the primary contributors to the plan and the national champion Huawei follows closely behind. Publicly traded firms like Alibaba play a considerably smaller role in the plan.

A low value-added trap

Beyond offering more flexibility in coordinating national-scale industrial policy, the diversity of ownership models in China’s cloud sector has resulted in far greater capacity for IaaS over PaaS. The growing presence of state-owned telecom firms has reinforced an IaaS-heavy model, as these companies are hardware-first enterprises with deep expertise in telecommunications infrastructure but limited experience in developing higher-value cloud services. On top of that, IaaS (compute infrastructure in particular) is also viewed as a critical resource only one level up from energy itself.

As a result, SOEs have focused on expanding data centers infrastructure, while making little contribution to building a robust cloud-native software ecosystems. This means that PaaS development is left primarily to the commercially oriented firms like Alibaba and Tencent. But even such investments are being punished by a market and state that continues to favor IaaS over PaaS.

This isn't helped by the fact that China’s cloud sector has over the past two years been engaged in a full-fledged price war, which has further incentivized firms to compete on low-cost infrastructure (IaaS) rather than higher-value services (PaaS). In 2023, Alibaba launched the largest price cuts in its history, slashing core product prices by 15% to 50%. Within a month, Tencent and JD.com followed with their own reductions. In 2024, Alibaba slashed prices once again, prompting immediate responses from competitors—including state-owned giants China Telecom and China Mobile. Unlike publicly traded firms, these SOEs are less constrained by short-term profitability because they benefit from state-backed patient financing, allowing them to sustain deeper price cuts for longer periods without the same risks faced by publicly traded firms.

From a long-term market perspective, price competition may be a natural stage of the maturation of the cloud industry as providers are able to take advantage of scale economies. A similar trend occurred in the U.S. cloud market with tit-for-tat price cuts between Amazon, Microsoft, Google, and IBM during the early 2010s.3 This made it impossible for smaller players to stay in the game, resulting in only a handful of viable cloud providers by the mid-2010s. China’s cloud industry appears to be following a similar pattern, where price competition becomes a strategic tool to drive adoption and expand market share. But the fact that the price war is only happening in China now suggests that the country’s digital transformation remains a full decade behind that of the United States. Moreover, these cuts come after the cuts already made in the West—meaning that Chinese cloud firms like Alibaba were price-competitive to their American counterparts before the full-out price war now taking place in China.4

Looking ahead, if China’s cloud sector follows the trajectory of its U.S. counterpart, we would expect a gradual shift away from a race-to-the-bottom price war toward higher-value services. This would mean moving beyond IaaS and focusing on PaaS and other higher-margin offerings. However, state intervention and the growing influence of SOEs could push the industry in a different direction. Rather than prioritizing profitability and premium cloud services, the Chinese government may continue to emphasize low-cost, commodity-like cloud infrastructure, particularly in alignment with national energy policies like Eastern Data, Western Computing. If this trend persists, China’s cloud sector may diverge further from the American model, focusing on state-led priorities over high-margin PaaS that is increasingly driving cloud profitability in the United States.

Conclusion

China’s cloud industry is at a crossroads. On one hand, state intervention and the growing presence of SOEs could significantly expand cloud infrastructure capacity, positioning China to narrow the gap with the U.S. On the other, persistent price wars and an overreliance on IaaS—coupled with weak competencies in PaaS and other higher-value services—risk locking China’s cloud sector into a low-margin, commodity-like industry.

On top of that, China’s underdeveloped PaaS offerings will make it even harder for its cloud providers to compete on a global scale. If they continue prioritizing cost-competitive infrastructure over higher-value software and platform services, they risk falling further behind in both profitability and global competitiveness.

To the Chinese state, however, this may very well not be the goal. Data—and by extension, compute—are seen as critical factors of production, akin to land and labor, making the cloud too strategic to be left entirely to the private sector. If this remains the case, China’s cloud sector will remain structurally distinct from its U.S. counterpart—more state-directed, possibly less profitable, but ultimately aligned with national priorities rather than besting the United States.

Normally, we might also look at Software-as-a-Service (SaaS), where we'll also find that, like PaaS, China's SaaS revenue is nearly negligible next to IaaS revenue. However, doing so would necessarily move our analysis away from the core of the cloud business model and force us to consider many other firms like Salesforce or SAP, which sit decidedly in a different category.

See Jonathan Woetzel et al., “China’s Digital Transformation: The Internet’s Impact on Productivity and Growth” (McKinsey Global Institute, July 2014).

Astoundingly, Amazon announced 44 price cuts in the span of 6 years according to Business Insider.

Its worth pointing out that this hasn't ignited a second round of price wars in the United States. Undercutting the west on prices, may push businesses in developing countries over to Chinese cloud providers, but will unlikely deter mature economies from staying with the established U.S.-based players.