The "China as superpower" vs "China in crisis" narrative

China's manufacturing prowess is sustained by the very conditions (low labor costs, minimal social policy, and currency devaluation) that create the sense of domestic malaise.

Media narratives about China can be dizzying. In one register, China appears as an unstoppable industrial superpower—dominating global markets for electric vehicles, solar panels, and batteries, and exporting these technologies at a scale and speed few countries can match. In another, it is portrayed as a country in crisis, plagued by youth unemployment, weak household consumption, and a pervasive sense of economic malaise (see figure 1). Particularly in Chinese media outlets, there are countless stories about young professionals "lying flat," educated graduates unable to find jobs, and increasing de-urbanization. To the casual observer, these conflicting accounts may seem irreconcilable. How can a country be both so dynamic and so distressed?

Part of the answer, of course, lies in China’s vastness. It is a country of immense regional, sectoral, and social variation—so it’s entirely plausible that multiple, even contradictory, stories about its economy can be simultaneously true. But I want to suggest something more: that this apparent contradiction may not be a contradiction at all but rather two sides of the same coin.

The idea developed in this post draws inspiration from the work of Matthew Klein and Michael Pettis, who have written extensively about trade imbalances and the structural features of China’s economic model.1 Building on their insights, my argument here is that the very conditions that have enabled China’s global industrial competitiveness are also the conditions that have produced its domestic economic fragilities. In other words, China’s export strength and internal weakness are not opposing realities but mutually reinforcing features of the same growth model.

To start, let me introduce the Growth Models framework developed by Lucio Baccaro and Jonas Pontusson.2 Their framework distinguishes national economies by their primary sources of aggregate demand: some countries are consumption-led, with growth driven by household spending, often enabled by credit or redistribution; others are export-led, where growth hinges on international competitiveness in tradable goods. The United States and United Kingdom paradigmatic cases of the former model; Germany is a classic case of the latter. These models are not just descriptive categories—they shape the behavior of firms, the preferences of policymakers, and the organization of institutions across the economy.

China, however, does not fit neatly into this framework—something Baccaro and Pontusson also acknowledge. While China shares key features with classic export-led economies like Germany, it has also relied heavily on investment in infrastructure and real estate to drive growth. Investment-led growth was particularly prominent after the 2008 global financial crisis when falling external demand prompted the Chinese state to unleash a massive stimulus into constructing infrastructure projects and property development. However, since President Xi Jinping, there has been a notable shift away from real estate-driven growth and toward reasserting manufacturing as the backbone of the economy, with an emphasis on strategic sectors such as electric vehicles, batteries, renewable energy, among others. This shift is slow, but China has come to more closely resemble a classic export-led economy, albeit with distinct characteristics shaped by its political system and development trajectory.

One of the key insights of the Growth Model framework is that export-led growth tends to generate weak domestic consumption, since maintaining competitiveness in price-sensitive global markets requires keeping wages down. This explains why, between the 1990s to 2000s, as the country shifted from a consumption- to an export-driven economy, German inequality rose sharply. During that period, German firms pursued various strategies to contain labor costs, but these efforts took place within a broader institutional environment characterized by strong employment protections and powerful trade unions, which helped preserve a degree of wage stability and social security.

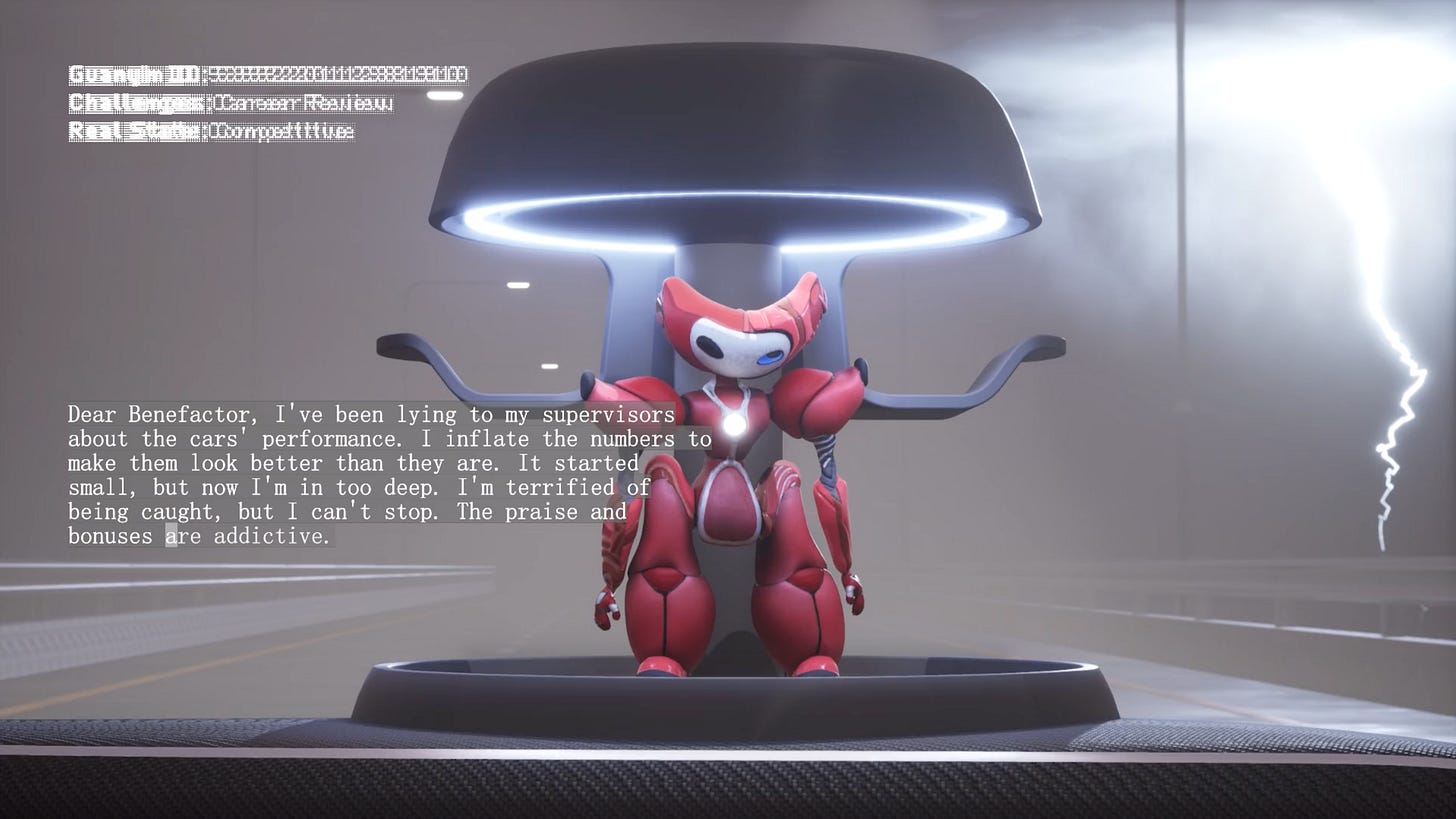

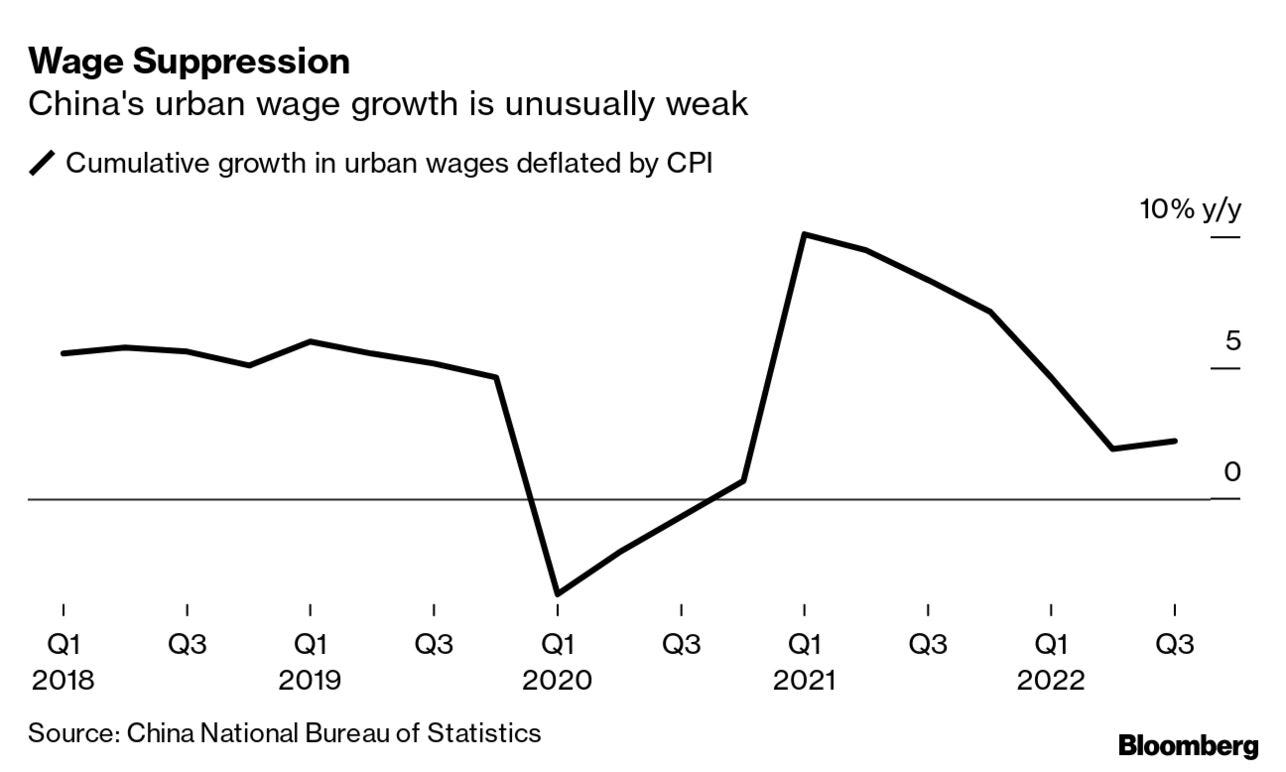

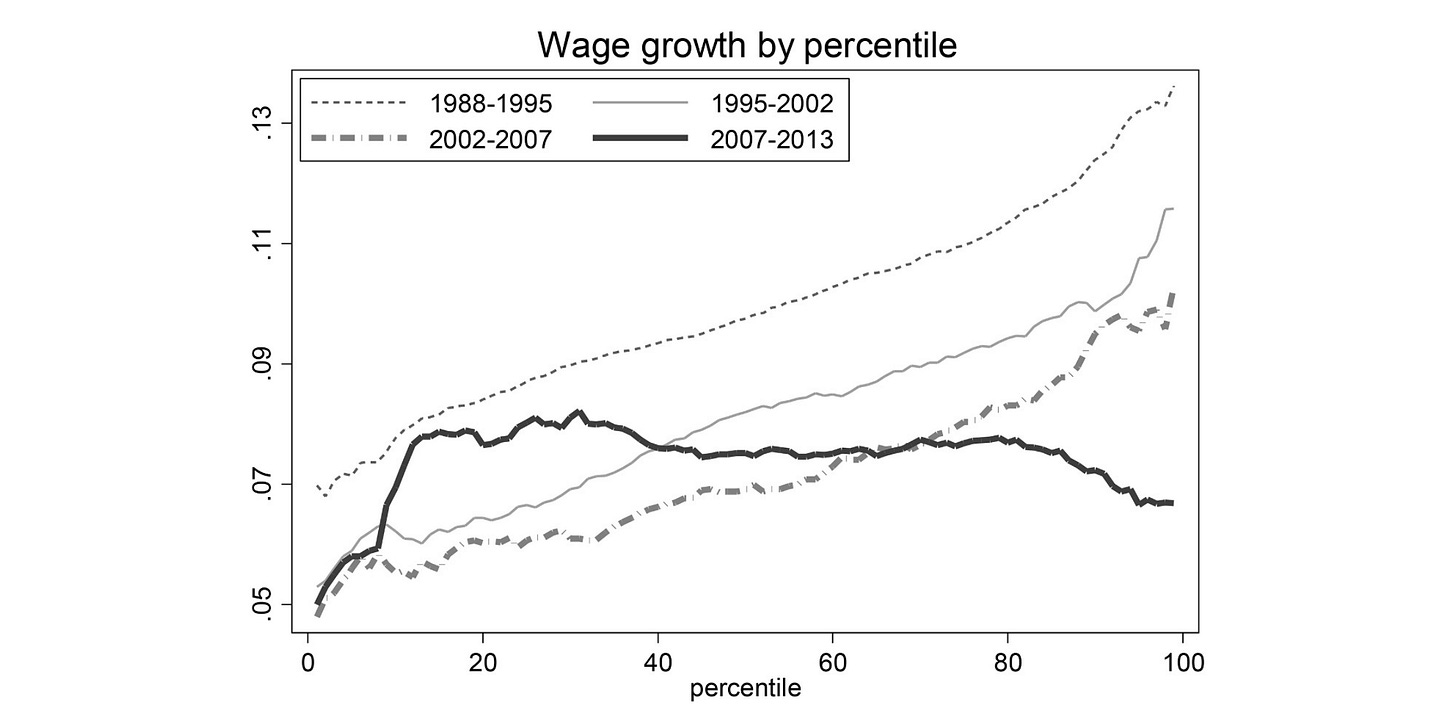

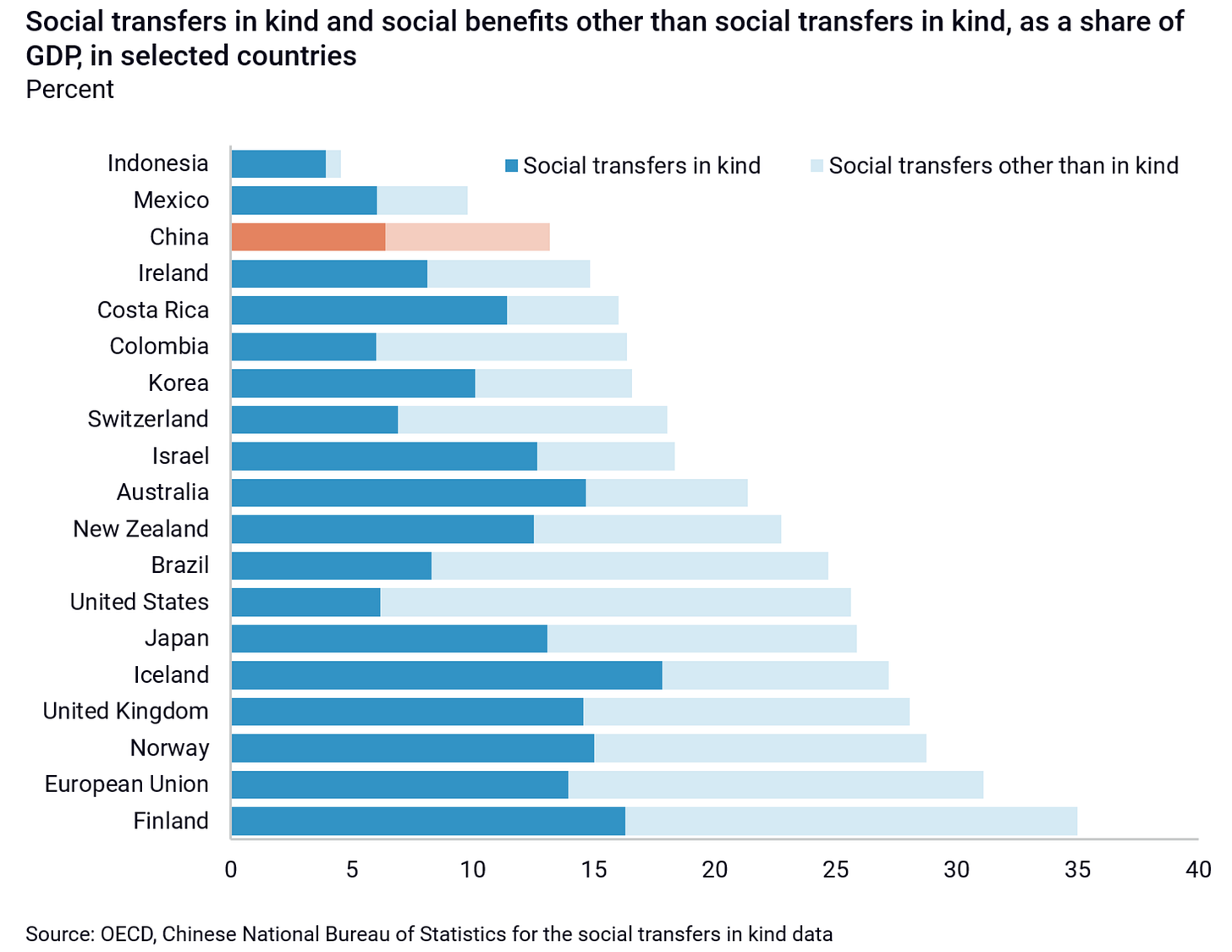

In contrast, China’s export competitiveness has been underpinned not only by wage suppression (see figure 2 and 3), but also by minimal social protection and weak labor institutions. Chinese firms benefit from a labor market where enforcement of workers’ rights and collective bargaining is virtually nonexistent. This institutional setup lowers production costs, but it also constrains household income and deepens reliance on external demand. The lack of a robust welfare state compounds the problem: with limited access to affordable healthcare, pensions, and unemployment insurance, households are forced to save more and consume less—in effect, a transfer from households to manufacturers (see figure 4).

Foreign exchange policy reinforces this pattern. For years, Chinese authorities have kept the renminbi undervalued relative to major global currencies. A weaker currency makes Chinese exports cheaper on world markets, but it also makes imported goods more expensive for domestic consumers. As with wage repression and limited social spending, this approach effectively operates as a hidden tax on households and a subsidy to exporters.

Of course, this is not the whole story behind China’s competitiveness in exports. In some of my other posts, I've tried to explain why Chinese firms lead in the production of emerging technologies—from economies of scale and state-led industrial policy to increasingly sophisticated supply chains and engineering capabilities. Still, these firm- or industry-level factors are couched within the structure of China’s growth model, which has created a cycle where global manufacturing competitiveness is sustained by the very conditions that constrain consumption at home.

Chinese solar manufacturing is a good example. To be sure, Chinese solar PV manufacturers are technologically sophisticated, and their export success owes much to decades of industrial policy, state subsidies, and coordinated support across the supply chain. But as more people turn to industrial policy as an explanation (myself included), what’s often-overlooked in explaining the competitiveness of Chinese solar manufacturers is their ability to keep the wages of relatively skilled labor low in labor-intensive production processes.

Recognizing that these contradictory narratives about China's economy stems from its growth model has several important implications. First, it challenges the common analytical impulse to interpret China through either a lens of technological triumph or looming collapse. This binary obscures the deeper structural logic of the economy. The very factors that explain China’s export competitiveness—low labor costs, minimal social policy, and currency devaluation—also explain its weak domestic demand.

Second, it suggests that strengthening domestic consumption may come at the cost of China's manufacturing prowess as it requires redistributing income toward households, expanding social welfare, and strengthening labor protections. This rebalancing is not simply a switch that can be flipped—but a politically contentious decision that would overturn China’s current growth regime.

Finally, it raises questions about the sustainability of this model, especially in light of renewed trade tensions. As countries erect barriers to Chinese products Beijing may find that its plans to export its way into ever higher GDP is running out of road. Without rebalancing its growth model, China risks becoming stuck: too dependent on exports to retreat inward, but too politically constrained to expand outwards.

(Coincidentally, while I was working on this post yesterday, Andrew of Sinocities published a completely different perspective that also explains China's bipolar character. I highly recommend checking it out, here.)

See, specifically: Klein, Matthew C., and Michael Pettis. 2020. Trade Wars Are Class Wars: How Rising Inequality Distorts the Global Economy and Threatens International Peace. New Haven ; London: Yale University Press.

Baccaro, Lucio, and Jonas Pontusson. 2016. “Rethinking Comparative Political Economy: The Growth Model Perspective.” Politics & Society 44(2): 175–207.