Tariff Wreckage: The Myth of America's Manufacturing Comeback

Trump’s tariffs promise industrial revival. Even if it does, it overlooks the simple fact that fixing American industry alone won't restore middle-class prosperity.

Trump has long cast himself as the savior of American manufacturing. This past week’s tariff frenzy is just the latest chapter in that story—billed by the White House and his supporters as the boldest move yet to bring industrial jobs back home.

Yet the volatility of Trump-era trade policy—abrupt tariff announcements followed by sudden reversals—has created an atmosphere of deep uncertainty for investors. For a manufacturer considering whether to build a new plant, the question is no longer just where to invest—whether in the U.S. or abroad—but whether to invest at all. Given the uncertainty under Trump, many firms may choose to delay major capital expenditures altogether, waiting for a more stable policy environment under a future administration.

But even with consistent trade policy, tariffs alone won’t do the trick. Without targeted industrial policy that can coordinate the rebuilding of productive capacity, tariffs will do more harm than good—raising consumer prices without meaningfully reviving U.S. manufacturing (I've written about this more in more detail here). The only scenario where tariffs might help is if they’re so extreme that it becomes cheaper to produce goods domestically than import them. But that would require far steeper rates than what’s currently on the table—and would come with serious economic side effects.

To be clear, I’m not arguing for higher tariffs. If anything, this obsession with tariffs reflects a deeper failure to grapple with an underlying assumption in Trump's diagnosis of the American political economy—that is whether or not bringing back manufacturing will generate the middle-income prosperity that Trump has promised.

Industrial decline in employment not output

There’s a reason manufacturing holds such symbolic power in American politics. For much of the 20th century, factory jobs were the backbone of the middle class. They provided steady employment, decent wages, and a ladder of upward mobility for millions—especially for workers without college degrees. Manufacturing was not just a growth engine; it was a social contract.

But that contract was underwritten by a very specific set of historical conditions: postwar U.S. industrial dominance, powerful labor unions, relatively self-contained supply chains, and a global economy still recovering from war. These conditions no longer exist—in part, this is because of changing firm strategies since the rise of the knowledge economy (which I wrote more about here). Unsurprisingly, manufacturing employment is now a fraction of what is used to be.

To explain America’s deindustrialization, politicians like Trump have turned to globalization and unfair trade, arguing that low-wage countries have unfairly attracted manufacturers and siphoned off well-paying industrial jobs. This narrative has since 2016 been a fixture in American political discourse, perhaps best seen in Trump’s rallying cry that “China is stealing our jobs.”

While there is no question that American jobs have been outsourced to East Asia, the extent of it is far overblown. Offshoring accounts for only a modest portion of the decline in manufacturing jobs.

Production facilities have since the late 20th century become capital-intensive, deeply automated, and designed to maximize output with minimal labor. Even in advanced industrial economies like Germany and Japan where manufacturing remains strong in output terms, there has been consistent declines in employment due to automation and other productivity-enhancing technologies. In this way, these countries remain a major manufacturing powers—not in spite of declining employment, but in part because of it.

To take a recent example, Texas Instruments plans to invest over $18 billion through 2029 in three new wafer fabrication plants in Texas and Utah. The initiative, however, is only expected to create 2,000 permanent jobs, alongside several thousand mostly temporary positions in construction and related sectors. The scale of investment simply does not translate into large-scale employment. So even if the tariffs worked and manufacturing does return to U.S. soil, the employment impact will be far more limited than Trump suggests.

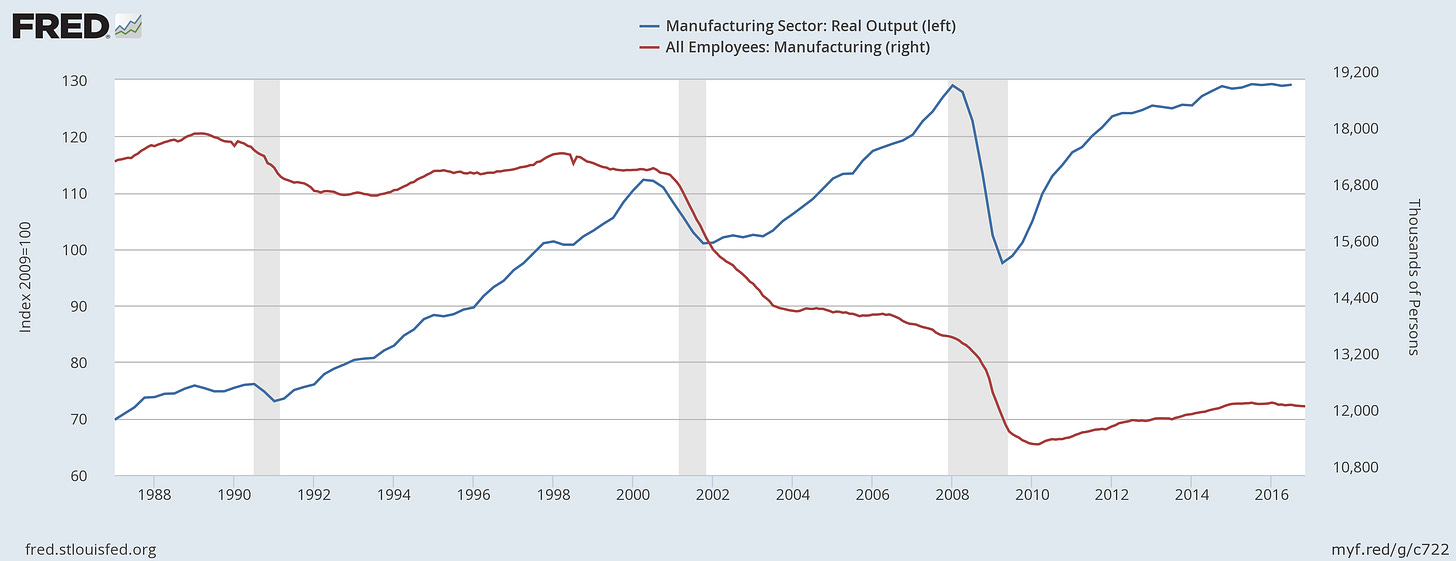

It also worth pointing out that while U.S. employment in manufacturing has faced a precipitous decline, the country's manufacturing output has actually increased over the past several decades. In fact, since the 1990s, manufacturing output has nearly doubled. That should remind us that what is often framed as a globalization problem—a story about the offshoring of American jobs—is in many ways a problem about technological change and the changing nature of manufacturing itself.

No revival without labor

Looking at employment underscores a larger point: even if manufacturing jobs were to return, there is no guarantee they would restore the broad-based prosperity associated with the postwar era. Much of the nostalgia for mid-century middle-class life rests on the fact that factory jobs were unionized, offering stable wages, strong benefits, and job security.

Before that, factory jobs were grueling, low-paid, and often dangerous. Workdays routinely stretched beyond ten hours, injuries were common, and basic protections were virtually nonexistent. Industrial cities were marked by overcrowded housing, poor sanitation, and slum-like living conditions.

The transformation of manufacturing into a source of middle-class security was not a natural outcome of industrialization itself—it was the result of decades of labor organizing, strikes, and political struggle. It was only through collective bargaining and the institutionalization of labor rights that manufacturing work became associated with “good” jobs.

This historical reality is starkly at odds with the current politics of industrial revival. The tariffs that Trump has portrayed as a solution to restore prosperity in America’s heartland obscure the central role that labor power once played in making manufacturing a path to upward mobility. Worse still, Trump’s vision of industrial renewal is often flanked by figures like Elon Musk, whose business models are built on minimizing labor costs, resisting unionization, and consolidating control over workers.

Concluding thoughts

There should be no illusion about the extent of industrial decline in the United States. The country has not only lost industrial jobs but also much of its industrial commons—the dense networks of suppliers, toolmakers, materials producers, and skilled workers that underpin productive capacity. Even the production of relatively simple goods can now pose significant challenges for the U.S.

There are good reasons to rebuild domestic manufacturing—chief among them, reducing dependence on fragile global supply chains in the face of disruptions like COVID-19. But we must be clear-eyed about what such efforts can realistically deliver. Restoring industrial capacity may be essential for strategic and technological sovereignty, but it is unlikely, on its own, to revive the broad-based economic security once associated with the American middle class.

In this context, it is crucial to distinguish between manufacturing’s role in boosting national productive capabilities and its declining capacity to generate employment at scale. Modern manufacturing is neither labor-intensive nor a panacea for job creation. And while tariffs may succeed in encouraging some domestic investment or even reviving elements of a new industrial commons, they cannot recreate the social contract of the mid-20th century industrial economy.

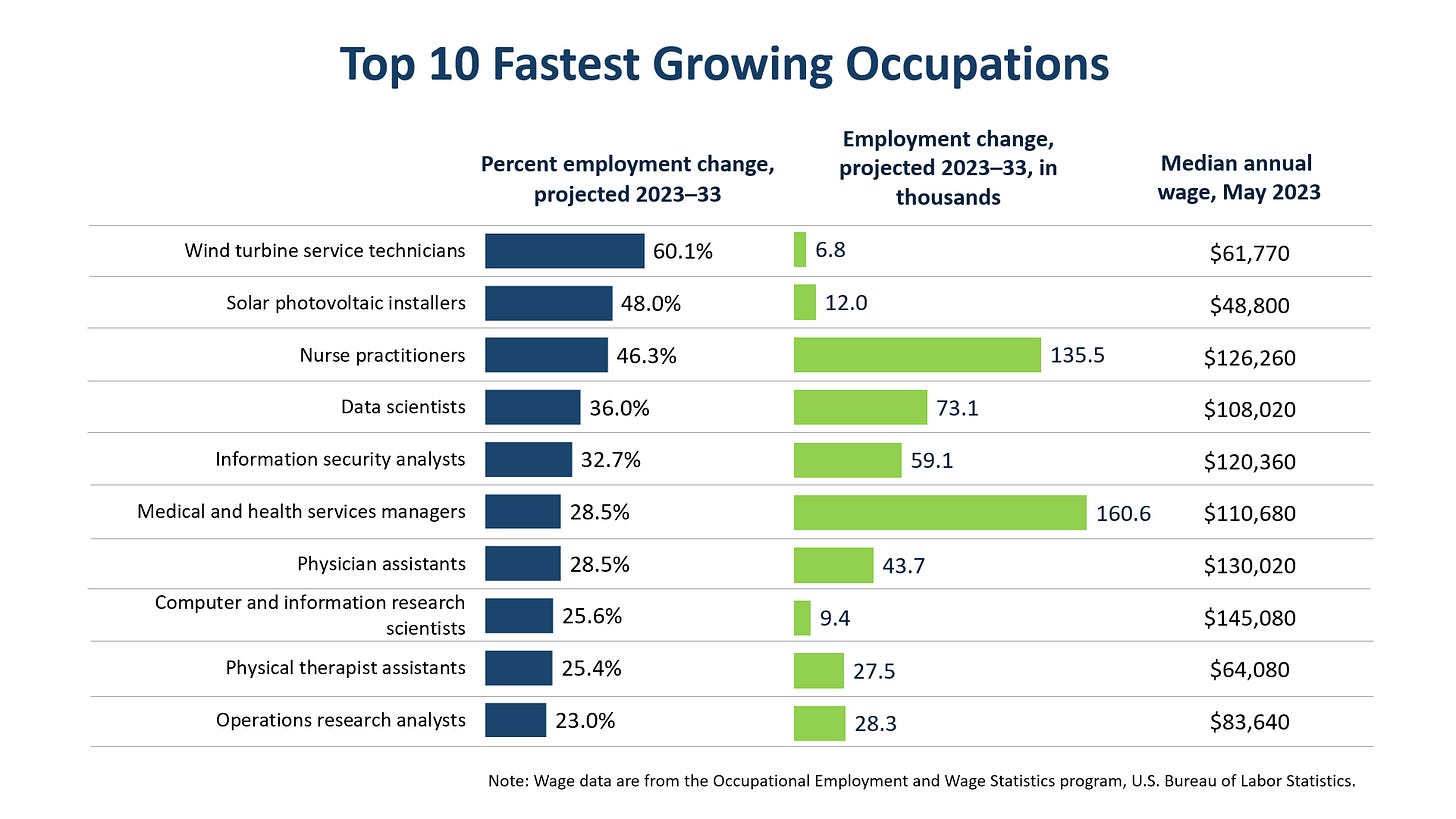

For that, we must turn our attention to the labor-intensive sectors where job growth is actually happening—care work, healthcare services, education, and green infrastructure. These sectors may lack the nostalgia associated with heavy industry, but they offer a far more plausible foundation for inclusive economic development in the 21st century.

Yet today, most of these jobs remain low-wage, precarious, and overwhelmingly non-unionized. Turning them into “good jobs” will require a renewed commitment to rebuilding labor power. Restoring broad-based economic security won’t come from bringing factories back alone; it will depend on empowering workers in the sectors that are shaping the future of the economy. That must be the center of any serious agenda for shared prosperity.

This is a really good essay, as usual but I have a few comments. The first is that this is about more than trade. The big problem for the US is that it cannot sustain its hegemony and very few people seem to understand what this really means. If the US can capture 90% of the value chain when they import manufactured goods, then their economy looks huge. But what if most of the value is really in the technology process? The thing that takes a long time to build (and I completely agree with your industrial commons point). So you lose knowhow, you lose diffusion, you lose learning etc; and all you have is a logo. Which people buy because 1. they have to trade in dollars and 2. the US is perceived as the powerful country. But 10 years from now, China will have a bigger military, a digital currency used exclusively for trade and a very high potential market (good demographics) clustered around the B&R nations. If you're a famous basketball star and you have the choice of slapping your logo on Nike or a Chinese brand - what do you care? So people in the US may look at that and think - God damn, if China runs its own trading area with its own trade currency, who's going to buy our debt? And if no-one buys the debt what's going to happen to the dollar? And the dollar falling would be fine ... if it meant cheaper exports. Except, what if it takes 10 - 15 years to build up the industrial commons to get there? In the meantime, all the service industries - banking, management consultancy, law firms are worth nothing to China. All of it gets cut out and the US is left with ... Europe, stagnating with an aging demographic.

So my main point is: they probably have to try and rebuild their manufacturing knowhow even if it doesn't translate into good jobs immediately. And my second, associated point is that GDP numbers are all based on $ hegemony. So, sure - 'manufacturing' has increased. But what that really means is that Apple, Nike whatever have captured the value chain. So they pay $10 for the import then slap on the logo and then add $200. GDP says: manufacturing has increased by $200. But it really hasn't. The market has grown and the market has grown because China reinvests its $10 take into US Treasuries to fund more $200 purchases! The really disappointing thing is that no-one on the Left has crafted a strong argument that is a version of the Trump story - i.e. you need to compete on equal terms now, not undercut our wages / currency etc; and we need to build strong, de-financialised companies with limited IP protection, modularity and strong trades unions. It is painful to see the Left get trapped in the same old arguments about capitalists vs workers. It should be production vs finance. End

Manufacturing output growth still visibly slowed down after 2000, which was really when China joined the WTO and manufacturing employment started declining. It has also been a declining share of gdp. Obviously this doesn’t say it’s trade not technology or something, but I think that people pointing at output is overstating their case.