How we forgot about production—and why it’s back on the agenda

A brief history of economic value from the factory floor to the platform economy.

Since the 1990s, the asset-light internet sector has been celebrated as the engine of economic dynamism. Companies like Microsoft, Facebook, Amazon, Netflix, and Google became the most valuable in the world and were widely hailed as the great value creators of our time. Meanwhile, companies engaged in manufacturing were downsized, offshored, and pushed to the margins of economic relevance.

In recent years, however, this trend has been put in reverse. Since Trump 1.0, the push to revive U.S. manufacturing has moved from the periphery to the mainstream. Through a series of industry policy packages, Biden directed billions into domestic semiconductor and renewable energy production to re-establish the U.S. as a manufacturing powerhouse. Even in today’s AI boom, profits are flowing not to software firms but to hardware giants like NVIDIA and AMD—a stark reversal of the high-margin software era.

A similar transformation is underway in China. The government’s 2021 crackdown on consumer internet firms marked a decisive pivot from internet services to “high-value-added manufacturing” in semiconductors, electric vehicles, and advanced robotics. More than just an effort to rein in the tech monopolies, this shift reflects a broader state ambition—not for better software, but for industrial strength. Today, the priorities can be clearly seen in Xi Jinping’s call for “new quality productive forces”—first outlined during his symbolic 2023 visit to Heilongjiang, China’s historic industrial heartland.

(This transformation has been central to my own research and interests, which I've written about here.)

To the techno-optimist, the shift from platforms to production might be puzzling. The platform economy has been an unparalleled engine of profit, so why are the U.S. and China actively pushing for a return to production? Many factors are driving this. For the U.S., re-shoring manufacturing is a matter of national security—an urgency heightened by the supply-chain disruptions of the Covid-19 pandemic and growing competition from China. For China, the push for advanced manufacturing is a strategy to export its way out of a persistent slump in domestic consumption.

But above all, the shift toward manufacturing is also a response to the distributional conflicts of the platform era. The platform economy has produced extreme wealth concentration while generating relatively few stable, well-paying jobs. So, as Dani Rodrik has argued, renewed interest in production reflects an effort to “work on the supply side of the economy to create good, productive jobs for everyone.”1 In this sense, the shift isn’t just about where profits are made—it raises deeper questions about how value was created and distributed under the platform economy.

The value of a platform?

For most goods and services, value is tied to the labor and materials required for their production. The work and resources put into each unit contribute directly to its cost and perceived worth. Software, however, operates under a fundamentally different logic. A programmer only needs to build a program once, after which it can be replicated endlessly at little to no marginal cost. Adobe, for example, can sell Photoshop subscriptions to millions of users without incurring additional production expenses beyond updates and maintenance.

This is even more pronounced in platform-based businesses. Take Uber: its value doesn’t come from producing a tangible good but from the number of riders and drivers on the platform—a phenomenon known as the network effect. The more people use it, the more valuable it becomes, without any fundamental changes to the service itself. Thus, unlike traditional industries, a platform's value isn't driven by scarcity but by scale, as each new user further increases the platform's utility.

In this sense, platforms don’t generate value in the traditional sense—they extract it. Their wealth comes from positioning themselves as indispensable intermediaries, charging fees/subscriptions for access to digital infrastructure. Many also profit by monetizing user data, selling targeted advertising, and acting as middlemen between producers and consumers—capturing profits without directly contributing to production.

This is where the disconnect becomes clear. In a traditional manufacturing economy, production is at the center of value creation—each additional car, appliance, or piece of furniture requires labor, raw materials, and industrial capacity to produce. But in the platform economy, value can scale without a corresponding increase in productive inputs. How did we arrive at an understanding of value where some companies can become fabulously wealthy without producing anything tangible?

In this post, I'll look at the history of the idea of economic value for some clues. I’m not suggesting that ideas about value directly drive economic transformations (in fact, I don’t believe ideas alone change much at all), but they play a crucial role in legitimizing and justifying such developments.

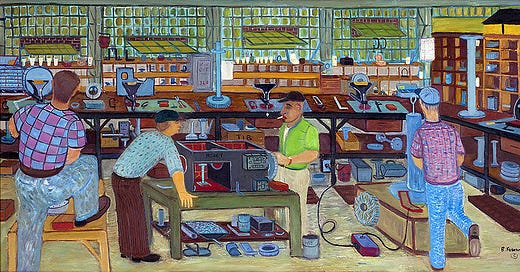

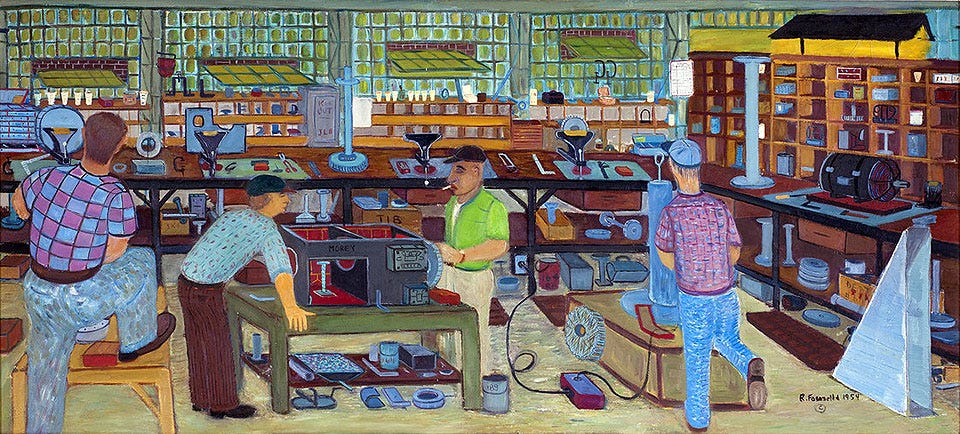

Production at the center of value creation

The concept of economic value was first interrogated in early attempts to measure a nation's wealth. In the 17th century, thinkers like Sir William Petty and Gregory King pioneered new methods of national income accounting, recognizing that production and expenditure were intrinsically linked. Yet, without a clear theory of where value came from, their categorizations of productive and unproductive work were inconsistent—Petty considered sailors and soldiers productive, while King saw them as unproductive. Both, however, understood that to explain why some nations grew rich while others stagnated, the question of value and where it came from needed to be answered.

The first serious claim to an answer came from the Physiocrats, an eighteenth-century group of French economists who were considered the first scientific economists. For them, value was rooted in the land. They argued that only nature could generate new wealth—grain from seeds, timber from trees—while human labor could merely transform what already existed. Farmers, miners, and other agricultural workers were thus seen as the true producers of value, while merchants, artisans, and laborers in other sectors were considered secondary.

While their theory may seem outdated in an industrialized world, the Physiocrats made a crucial intellectual breakthrough: they explicitly linked production to value creation, laying the groundwork for what came next.

A labor theory of value

Classical economists such as Adam Smith, John Stewart Mill, and David Ricardo also obsessed over productive versus unproductive activity, but instead of attributing value creation to the land, these economists located value as arising from human labor. Writing at the dawn of industrial capitalism, they observed that value wasn’t generated in the fields but on the factory floor, where workers actively transformed raw materials into goods. To Smith, the merchant who simply moved goods around did not create value; nor did the landlord who collected rent. Value was the result of productive labor.

This perspective gave rise to the labor theory of value, which argued that value was embedded in the labor required to produce a good. What often gets misrepresented about Smith is his view on markets. While he championed free trade as a mechanism to encourage productive activity and expand national wealth, his idea of a “free market” was one free of rents. Smith was a harsh critic of rents, which he believed was a hindrance to economic growth. Ricardo took this critique even further, warning that unchecked rents would lead to a lopsided economic system where landlords captured an ever-growing share of wealth without contributing to production.

Building on the classical economists, Karl Marx pinpointed exactly where in the labor process value originates. He argued that new value (surplus value) arises from an unequal exchange between workers and capitalists. Workers provide more value in production than they receive in wages, and that surplus is extracted as profit. Surplus value is then congealed into the commodity and remains neither visible nor consumable until sold in the marketplace at which point it gets realized as profits. This theory of value clarifies the role of the market. Rather than seeing value as originating in exchange, Marx argued that the market is where surplus value (created outside of the market) is realized as profit.

(Update: In the comments section of this post, davide of critic of political economy wrote a useful note that highlights the distinction between Marx and Smith/Ricardo in their approach to understanding value).

Whether it was Smith or Marx, the distinction was clear: industries that produced value expanded the economic pie, while those that extracted rents merely redistributed wealth without creating anything new.

(I've written about why manufacturing has the unique ability to drive economic development here)

The Marginalist Revolution

In the late 19th century, a new theory of value emerged. Unlike the classical economists and the Physiocrats, who linked value to production—whether from land or labor—this new school of thought, known as marginalism, severed value from production altogether. Under this new economic paradigm, the price of a good or service commands on the market becomes the ultimate measure of its worth. As a result, value appears to originate in the act of exchange rather than in the process of production.

The key distinction here is that value is not created in production but is the result of how a good or service is priced. As such, profit is not seen as the outcome of value creation but is itself equated to value. Without a theory of value that can distinguish where value comes from versus how it gets realized, all economic activity is folded into the logic of marginal utility. And so rents, once seen as unproductive and parasitic, are redefined as a value-creating activity.

The marginalist project was not merely an intellectual shift—it was also a political one. By redefining value as a function of individual utility rather than labor, it depoliticized economics by shifting attention away from production and class relations. This reframing stripped labor of its central role in value creation, undermining the theoretical foundation for worker power. For financial elites and industrial capitalists resisting calls for labor protections, marginalism provided a powerful ideological tool that legitimized profit as a market outcome rather than as the product of work.

This understanding of value underpins the platform economy. Platform firms generate wealth by positioning themselves as intermediaries between buyers and producers, extracting rent from each transaction. So even though they don't directly contribute to production, their rents-based profits are written off as a form of value creation.

(I've also explored the intellectual history of industrial policy and how ideas stemming from the Marginalist Revolution led to its demonization.)

Concluding thoughts

This brief history of economic value should remind us that the concept has been fiercely contested for centuries. And that it was only during the Marginalist Revolution, that the distinction between creating value and extracting/circulating was abandoned. Yet today, marginalism is so deeply embedded in mainstream economic thought that its ideas are treated as fundamental truths rather than historical developments. This has given us the illusion that activities like financial speculation or platform rents are no different from production.

Today, the pendulum is swinging back. The shift from software to manufacturing represents more than just a sectoral rebalancing—it signals a potential return to an economy rooted in production. In a world where workers are increasingly excluded from the economic gains of the platform economy, this shift should, in theory, re-anchor economic value in labor, reversing decades of wealth concentration in asset-light, rentier industries.

But whether this revival of production translates into good, well-paying jobs—or merely accelerates the subordination of labor to AI, automation, and algorithmic management—remains to be seen. As industrial production becomes increasingly automated, the growing risk is that this new industrial age will be defined by machines outnumbering workers, reproducing the same lopsided distribution of economic gains.

See: Rodrik, Dani. 2023. "On Productivism." https://drodrik.scholar.harvard.edu/sites/scholar.harvard.edu/files/dani-rodrik/files/on_productivism.pdf↩︎

Great piece, and super excited to people taking about value theory. It fell out of favor because people either didn't understand the stakes at play, or thought it was about ethical/moral perspections of what should be 'valued'. I have a few comments:

I think the movemet from 'software' to 'hardware' shouldn't be see as a movement from sort of 'fictious' to real value (don't think you're implying that but many do). I think the shift isn't towards production, but rather maybe the production of goods vs services, as there's reason I think the former may be more stable in some senses due to the material differences that both production processes entail.

Software is a good, but it's a good that doesn't fit as well into capitalist relations in some senses. On the one hand as you state, software like knowledge takes little to reproduce and thus can be applied productively (what marx would call a free gift). This requires the rise of intellectual property, because there's so much threat of theft. Therefore, the production of physical goods and serivces allows for better control of private property. But the issue is that we do need software often, and it's an advacement that capitalism has brought. The blurring lines between software as a good v service are important to making these sectors continually profitable.

Also, in terms of the 'value' of companies, I do think we need to also seperate the fact that market-value of firms is always future oriented, and thus, creates a project of what the future 'value produced' might be. Unlike a lot of crude heterodox approaches that see this as fictitious, it is not completely based in a fictious (not much more than capitalist value in general is, which is misunderstood by th capitalist). If we look some examples of platforms, they are larger reoganizations of the labor process which allow for the extraction of value. Because you can't really make travel more productive, Uber is really about increases surplus extraction and thus profits. But some platform companies produce intellectual knowledge from which they then seek to extract surplus. It's a mix, but I thik the naunce is important nonetheless.

I agree that the shifts are due to political and class conflicts that are requiring the reconstitution of our current regime of accumulation. I think the hegemony of tech firms in their current form was based on the stability of the geoplitical system which allowed for industrial manufacturing to safely exist within a national-based international division of labor. As you show, this is rapidly changing. It's incredible how the division of ownership and control within the industrial circuit that has constituted the platform economy is very close to what Stephen Hymer predicted, in particular the value capturing by the global north. He argues this in his groundbreaking essay on the internationalization of capital https://www.jstor.org/stable/4224124.

Finally, I want to make some corrections about Marx's value theory, which I think needs to be seperated from the labor theory of value. First, Marx doesn't think that surplus value comes from an unequal (formal) exchange between capital and labor, in fact, it's the opposite. That's because the laborer doesn't sell their labor (the value of the full product as a result of their laboring) and just gets screwed. No, they sell their labor-power i.e. their capacity to labor. That's why the capitalist in paying workers doesn't steal their value in exchange, it's the fact that they are the owners of the means of production and have the right to the end products of the capitalist production process that they can appropriate surplus value.

This is important, because as Marx is trying to show, Smith and Ricardo often have a contradictory theory because don't see that the laborer is paid the value of their labor-power and not labor. Smith for example goes back and forth between labor being paid its 'value' like capital and land, and then back to labor being the only source of value. The issue is that detractors today simply say "well the wage is the value of labor, capitalist are paid for their work" when in fact the capitalist isn't necessary but the worker is (in terms of the labor process). The exchange is formally equally, but in essence, the capitalist accumulates surplus that is taken from labor.

While I think there's a lot of interesting nuances, I don't think we can say we are returning to production, but that production is again changing its content (the type of use-values being made). I think the pure deliniation between 'extractive' and 'productive' capitalists is problematic, and needs to be challenged a little more. I hope to add to this conversation soon, keep up the stuff I love reading your work!