From Fordism to the Platform Economy: The Evolution of Firm Strategies

How firms went from building it all to building nothing at all.

Many of my posts have explored the interaction between firms and the state—interrogating how industrial policy and the institutional configurations of national economies shape firm performance and innovation. I’ve written about how green industrial policy intersects with systems of interest representation (pluralism vs. corporatism), how state support influences talent acquisition in emerging technologies, and how different labor regimes steer the commercialization of AI. In each case, the state has functioned as the independent variable that drives outcomes in firm strategy or innovation (the dependent variables).

But any serious analysis of the political economy of innovation must also account for the other side of the equation: the firm itself. How firms are governed, how their business models evolve, and how strategic choices are made matter just as much. That’s what this piece focuses on—firm strategies and how the frontier corporations in advanced countries like the United States went from building it all to building nothing at all.

To understand this transformation, we need to understand how leading corporate strategies have change—beginning in the 1970s, where a series of seismic shifts took place. Where leading firms used to be vertically integrated and asset-heavy, today, they are vertically disintegrated and asset-light. In this post, I’ll chart the evolution of corporate strategies and conclude with a brief discussion about the distributional implications of such a transformation.

Labor peace in the early-mid 20th century

The Fordist firm is the "build it all" kind of firm, making it a natural place to begin our story. Fordism emerged in the early 20th century with Henry Ford’s revolutionary approach to automobile manufacturing. It refers to a model of mass production characterized by standardized goods, assembly-line techniques, and stable employment contracts—often tied to mass consumption.

This model defined the industrial landscape for much of the century. Supply chains were vertically integrated, with apex firms overseeing every stage of production, from raw material extraction to final assembly. Competitive advantage hinged on economies of scale, which required patient capital—typically provided by banks or passive investors willing to support long-term growth. Within these firms, managerial planning prioritized stability, steady expansion, and internal coordination over rapid disruption.

The unique arrangement between employers and workers was at the heart of this mode of production. This model hired unionized workers that enjoyed extensive benefits and high wages, supporting a middle-class standard of living. Firms employed large numbers of workers in massive, geographically anchored production sites.

This combination of high fixed costs and labor-intensive work made Fordist firms vulnerable to labor unrest, incentivizing employers to make peace with unions and share the rewards of their gains with their workers. As a result, this era saw a relatively stable form of capitalist production. Profits came not from slashing wages to cut costs but from investment in productivity-raising technology.

The Shareholder Value Revolution

The Fordist model—and the labor peace that came with it—began to unravel in the inflationary 70s. Rising prices, stagnant growth, and intensifying competition from lower-cost international producers, especially in Germany and Japan, put pressure on the vertically integrated, domestically rooted firm. In response, companies began outsourcing production abroad, breaking apart traditional supply chains in search of cost efficiencies. This marked the breakdown of Fordism and set the stage for a dramatic evolution in American corporate strategies.

A key part of this shift was the financialization of the American political economy—a transformation that Fligstein & Shin call the Shareholder Value Revolution.1 In this new financial paradigm, firms oriented themselves around the short-term maximization of stock prices, leading to new corporate strategies that prioritized shareholders' interests over other stakeholders, including workers and management.

Traditionally, stock prices were largely influenced by a company's profitability and dividend payouts. However, during the 1990s bull market, this dynamic shifted, especially in high-tech sectors, where investors began focusing more on future profitability than current earnings. Consequently, stock prices started to rely heavily on Wall Street analysts' forecasts rather than present-day financial performance, prompting managers to become increasingly fixated on meeting the profit targets set by analysts.2

Part of this transformation came from a new management paradigm centered on "core competencies." In theory, this new approach emphasized the development of strategic resources and capabilities crucial to a business's competitive edge. In practice, however, it translated to cost-cutting measures through extensive outsourcing and offshoring of the supply chain. This organizational shift epitomized the "break it up and sell it off" mentality, leading to the fragmentation of firms that were once consolidated and vertically integrated—a process David Weil describes as fissurization.3

This new era of fissurized governance led to the erosion of organized labor. Where the Fordist period was characterized by strong unions and an even bargain between labor and capital, the new strategy—empowered by a neoliberal political climate—was for firms to take every opportunity to reduce wages, cut benefits, and decrease the size of their workforce. Unions were undermined, and production shifted to regions abundant in inexpensive, low-skilled, and highly exploitable labor. This enabled U.S. firms to replace standard employment arrangements with more precarious ones and outsource functions outside their supposed "core competencies."

Part of the turn away from skilled labor came from divestment from productivity-increasing capital expenditures, turning once capital-heavy firms into asset-light firms. Following this divestment in capital assets, capacity utilization in US manufacturing has steadily dropped since the 1960s.4 In the inflationary 1970s, an environment plagued with uncertainty and risk aversion, companies prioritized everything but reinvesting in capital growth: share buybacks, dividends, and mergers and acquisitions exceeded capital expenditure. In other words, firms divested from precisely the features that could sustain long-term competitiveness and durable growth in exchange for short-term gains in financial markets.

The rise of intangibles

As the transformation to the fissurized firm was underway, another development was taking place: the ICT revolution. In many ways, the ICT revolution intensified the changes in the corporate strategies described above. Networked technologies allowed firms to communicate with and manage suppliers from afar. Advancements in shipping technologies allowed supply chains to further fragment across borders. And digitization enabled firms to offshore workers while maintaining control.

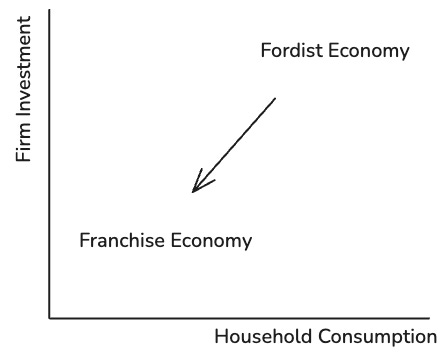

According to Herman Mark Schwartz, the primary implication of the ICT revolution is a shift in the preeminence of intangible over tangible production, creating what he calls the franchise economy.5 The apex firm in this new economy is the franchise firm that seeks monopoly profits through control of intellectual property rights (patents, copyrights, brands, and trademarks)—rights that must be recognized and enforced by the state. And unlike the vertically integrated firms from the 20th century that controlled both the knowledge, physical capital, and labor required for production, these elements of production are separated under the franchise economy.

This separation enables a three-layered hierarchy of production:

Knowledge-intensive firms that produce the intellectual property

Physical capital-intensive firms that handle value-added production

Labor-intensive firms that disciplines and exploits cheap labor

The production of the iPhone is emblematic of this three-layered hierarchy. Apple produces the iPhone's design and its associated patents, putting it at the top of the hierarchy. Firms like Qualcomm and Intel are in the middle layer because they produce the physical capital-intensive parts of the iPhone, such as semiconductors. Foxconn, responsible for assembly and other low-end tasks, is at the bottom of the hierarchy. This fragmentation allows the top firm—the franchise firm—to capture most of the profits by controlling IP while outsourcing the risk and costs to the lower layers.

The platform firm business model

ICT technologies have also enabled the rise of a new kind of digital enterprise: the platform firm.6 In many ways, the platform model amplifies features already present in the fissured economy. These firms take asset-light strategies to the extreme. Rather than owning physical assets, they operate as intermediaries—controlling access to markets while offloading risk and responsibility. Take Airbnb, for instance: instead of owning real estate, it sets the rules of engagement (and takes a substantial cut) for property owners who want to tap into its global network of vacation-goers.

Platform firms also push the logic of labor flexibility even further. Instead of simply outsourcing to low-wage regions, they use technology to “gigify” work—transforming stable jobs into fragmented, on-demand tasks that bypass traditional labor protections. In fact, platform workers such as drivers for Uber and Lyft are some of the most exploited workers in advanced countries like the U.S. Many are immigrants, living paycheck to paycheck, and their wages are subject to the whims of pricing algorithms. Legally, these platform drivers also have little to no ability to advocate for better pay or working conditions.

In other respects, platform firms diverge sharply from earlier post-Fordist strategies. Because a platform’s value depends heavily on the size of its user network, firms are driven to pursue market dominance at all costs.7 This dominance not only generates a steady stream of rents but also creates high barriers to entry, turning network effects into a source of enduring competitive advantage. As a result, platform firms are often willing to forgo short-term profits in favor of aggressive growth, betting on winner-take-all dynamics that promise outsized returns down the line.

This growth-at-all-costs model is backed by investors who prioritize market share over immediate profitability. In many cases, they actively subsidize platform expansion—underwriting the costs of acquiring users and squeezing out competitors. For example, Uber subsidized drivers and riders to beat competing platforms such as Lyft, allowing it to develop its self-reinforcing cycle of more supply (drivers), leading to more demand (users).

This table summarizes the firm strategies outlined above.

How these frontier corporate strategies produce widespread stagnation

While each post-Fordist model differs in its specifics, the overall trend in corporate strategies has been to focus not on productivity-enhancing investments but on easy profits that rely on cost-cutting measures, outsourcing risk, and eroding labor. The fissurized model outsources labor to the Global South and adopts an asset-light corporate strategy. The platform and franchise model abandons physical production altogether, relying instead on market dominance or legal monopolies—strategies that allow firms to extract rents with an even lighter asset footprint.

In the 20th century, the primary distributional conflict was between labor and capital—and this conflict was mediated by strong unions who bargained a fair deal. Today's corporate strategies have concentrated profits within a few dominant firms, shifting the axis of conflict from within firms to between them. Intellectual property rights create a legal monopoly for franchise firms to generate steady profits, giving them little incentive to reinvest in expanding their capabilities. Similarly, dominant platform firms can collect rents from users without incurring additional costs. Paradoxically, we end up with record profitability among the top firms but an overall decline in capital investment and innovation.

In other words, profits are increasingly concentrated at the top—but because the dominant corporate strategies prioritize financial engineering, outsourcing, and rent extraction over productive investment, those profits are among the least likely to be reinvested.

Schwartz shows that before 1980, the top 100 firms reinvested their profits into capital expenditures at significantly higher rates than the average firm.8 Today, however, that pattern has reversed: the largest firms now reinvest at lower rates than the average, signaling a broader retreat from productive investment at the corporate frontier. This shift has far-reaching consequences. As capital accumulation becomes decoupled from investment and growth, wealth is concentrated in an ever-smaller circle. And because wealthier households have a lower propensity to consume than poorer ones, this concentration dampens overall household demand.

Concluding thoughts

The evolution of corporate strategy is a story of shifting organizational logics—of firms adapting (or reinventing) their models in response to changing pressures and opportunities. Under the Fordist model, vertically integrated automakers built it all. Since then, most automakers have moved in the opposite direction—focusing on design and final assembly while outsourcing the rest.

Today, however, a new trend is emerging: automakers like Tesla and BYD are vertically integrating everything from battery production to electric powertrains and proprietary software, reviving an older industrial logic in this new technological era. The surge in data center investment across the tech sector likewise marks a reversal of the past four decades of asset-light strategies—signaling a renewed emphasis on physical infrastructure and long-term capacity.

The post-pandemic reshoring of supply chains, growing geopolitical tensions between the U.S. and China, and the intensifying urgency of climate change are all pushing firms back toward tangible production and long-term planning. The conditions that gave rise to the asset-light model may be fading but whether this leads to a fundamental reimagining of firm strategies—or merely tweaks to the current paradigm—remains to be seen. Ultimately, the kind of innovation we get depends on the kind of firms we allow to dominate.

Fligstein, Neil, and Taekjin Shin. 2007. “Shareholder Value and the Transformation of the U.S. Economy, 1984–20001.” Sociological Forum 22(4): 399–424.

See Zorn, Dirk, Frank Dobbin, Julian Dierkes, and Man-Shan Kwok. 2005. “The New New Firm: Power and Sense-Making in the Construction of Shareholder Value.” Nordiske Organisationsstudier 3: 41–68

Weil, David. 2014. The Fissured Workplace: Why Work Became so Bad for so Many and What Can Be Done to Improve It. Cambridge, Massachusetts London: Harvard University Press.

See Schwartz, Herman Mark. 2022. “From Fordism to Franchise: Intellectual Property and Growth Models in the Knowledge Economy.” In Diminishing Returns, eds. Lucio Baccaro, Mark Blyth, and Jonas Pontusson. Oxford University PressNew York, 74–97.

Schwartz, From Fordism to Franchise

For more on the platform firm business model, see rahman(s)-thelen(k)-2019Rahman, K. Sabeel, and Kathleen Thelen. 2019. “The Rise of the Platform Business Model and the Transformation of Twenty-First-Century Capitalism.” Politics & Society 47(2): 177–204

See Srnicek, Nick. 2017. Platform Capitalism. Cambridge, UK ; Malden, MA: Polity.

Schwartz, From Fordism to Franchise

Very interesting piece, I'm interested in the debate as to whether firms are themselves really investing less or if it's also changed. There's a focus on capital investment, but other authors like Maher and Aquanno argue that R&D per GDP hasn't lowered per say. I am in the middle where, we have to explain why northern capitalism has stopped growing, but I don't think it's as simple as monoply + stagnation.

Well written, I would note that prior to the post WW2 centralization that culminated in the advent of the so called Neoliberal Era we were also politically, economically, governmentally, financially, and scientifically decentralized system that proactively, at different levels of government made things the way they were and took proactive steps for hundreds of years, especially at the state and local levels, to prevent the financialization of the economy