Are data centers a new growth engine for developing countries?

The Malaysian government is counting on attracting data center investment to transform the country into a digital powerhouse. But is this a viable path that can enable broad economic development?

The rise of generative AI, with its insatiable need for compute power, has turned data centers into a critical battleground in the ongoing U.S.-China tech competition. For some developing countries, this moment presents a new growth opportunity: attract the tech giants, host their data centers, and leap into the digital future.

Malaysia—long stuck in the middle-income trap—has jumped on precisely such an opportunity. Late last year, its government approved a new set of Data Center Planning Guidelines aimed at standardizing and streamlining the data center development process. The goal is clear: make Malaysia a regional hub for data center investment.

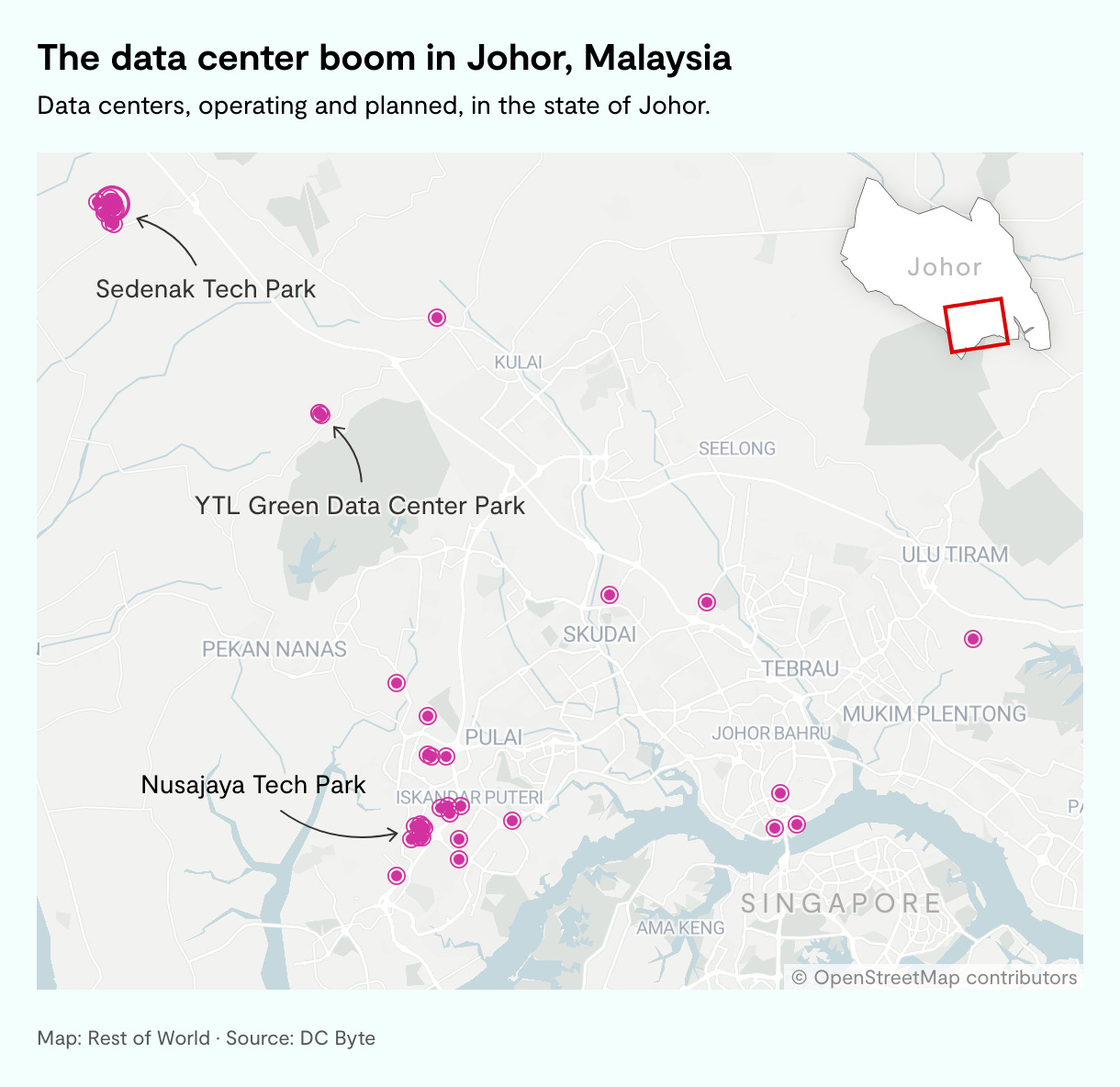

Some of the pieces are already in place. Alibaba Cloud operates facilities in Johor, Malaysia, but the real investment is coming from U.S. firms. Amazon is planning to invest $6.2 billion. Google: $2 billion. Oracle: $6.5 billion. In 2024, the country attracted over $31 billion in investment in data centers. For Malaysian officials, this flood of foreign investment is not just a vote of confidence—it’s the catalyst for economic transformation that they're hoping will catapult the country into a digital powerhouse. But will data centers generate the kind of broad-based growth needed to pull Malaysia out of the middle-income trap?

Its easy to equate economic growth with capital inflows. Investment, after all, is key to development. But as countries move from lower- to middle-income, what matters just as much as the quantity of investment is its quality—how it shapes labor markets, industries, and state capabilities. In this post, I turn to ideas in development economics to assess whether data centers can serve as viable engines of structural transformation—or whether they risk reproducing old dependencies in new digital clothes.

Features of a growth engine

To understand whether data centers are developmental, it’s helpful to begin with a sector that unquestionably was: manufacturing. In the 20th century, manufacturing served as the ladder to high-income status for a wide range of countries—from early industrializers like Germany and the United States to the postwar developmental states of Japan, South Korea, and, most recently, China.

What makes manufacturing so effective? First, it supercharges productivity growth—both across and within sectors. Arthur Lewis famously argued that development occurs when surplus rural labor is absorbed into the modern sector, particularly into urban factories where production benefits from economies of scale, technological upgrading, and organizational discipline.1 Manufacturing not only raises the output per worker, but also formalizes labor relations and embed workers into more productive value chains. More recently, Dani Rodrik observed that manufacturing exhibits a unique trait among economic sectors: unconditional convergence in labor productivity.2 That is, manufacturing firms in low- and middle-income countries tend to catch up with their counterparts in high-income countries regardless of their starting point, especially when exposed to export markets and global competition.

Productivity is only part of the story. Manufacturing also creates extensive linkages—a concept popularized by development economist Albert Hirschman.3 Hirschman argued that the most catalytic sectors are those that generate strong forward and backward linkages. The automobile industry, for instance, creates backward linkages by demanding a wide array of inputs: steel, rubber, glass, electronics, and complex machinery—spurring investment in upstream industries across multiple domains. It also generates forward linkages by producing vehicles that serve as critical inputs for downstream sectors such as logistics, public transportation, and delivery services. This stands in contrast to sectors like services, where outputs are typically consumed where they are produced.

(I've written more on manufacturing and economic development here)

Is the data center the new factory?

Do data centers offer the same developmental benefits that manufacturing once did? The first measure that usually comes up is job creation. Rest of World reports that Malaysia’s data center boom has already generated around 40,000 jobs—a figure that sounds impressive on its face.

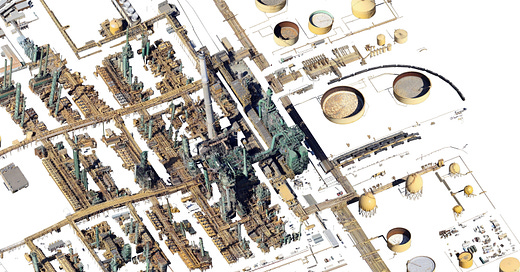

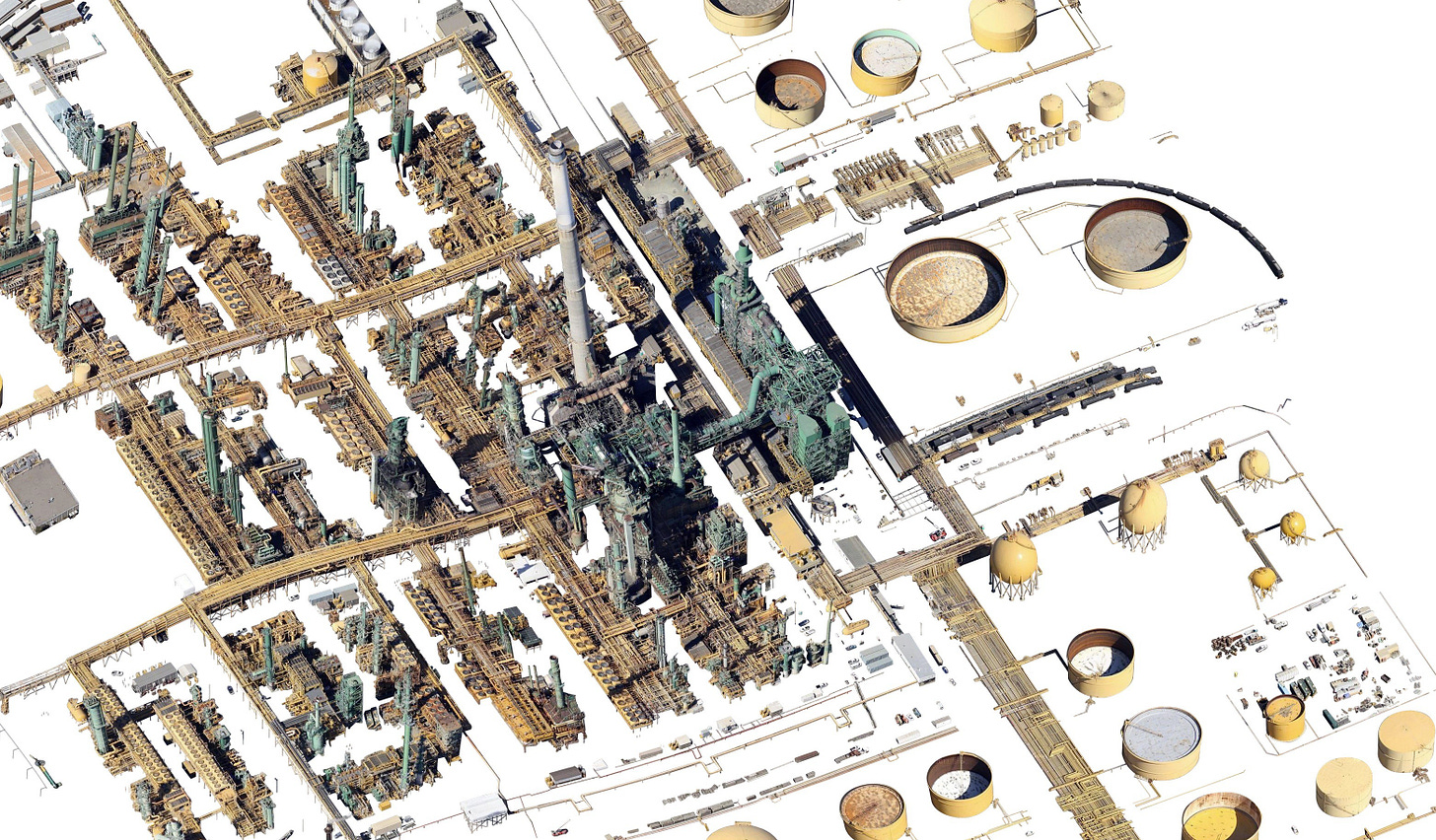

The reality, however, is that many of these are short-term construction jobs. Building out a hyperscale data center requires a small army of contractors—electricians, steelworkers, HVAC technicians—but once the facilities are operational, employment drops off sharply.

Unlike industrial factories, data centers are not labor-intensive. They are typically operated by small teams of highly specialized workers: network engineers, systems administrators, and facility managers. Security guards and janitors are also required for ongoing maintenance. Combined, these workers amount to only 30-50 permanent jobs (the largest facilities rarely exceeding 200), according to a report by the American nonprofit Good Jobs First. These roles are often high-skill—and unless the host country has a strong domestic pipeline of these specific skills, they are likely to be filled by foreign expertise.

Without deliberate state intervention to build local capacity, the risk is that data centers become enclaves: high-tech, foreign-owned, capital-intensive, and ultimately disconnected from the local labor force.

Downstream linkages

This brings us to our next question: do data centers produce an abundance of forward and backward linkages? Recent industry reports tout the idea that data centers generate a "halo effect," attracting downstream digital industries such as software development, cloud services, and AI research. The argument is that proximity to high-speed, low-latency infrastructure will stimulate innovation, encourage digital clustering, and create a more dynamic local tech economy.

But the evidence for this effect is thin. One of the defining features of cloud computing is that its users can access it remotely, from anywhere in the world. There is little reason for a software startup—or even an AI research lab—to be physically located near the data center it uses. Even for the most computationally intensive workloads, such as AI model training, what’s required is access to large-scale compute—not physical proximity. The underlying infrastructure may be local, but the innovation it enables can (and usually does) occur elsewhere.

Consider Loudoun County, Virginia, which has the highest density of data centers in the world and serves as a core hub for Amazon Web Services. If the halo effect were real, we would expect to see a vibrant tech ecosystem growing alongside this infrastructure. Yet despite billions of dollars in investment and dozens of hyperscale facilities, the region remains a logistics and real estate hub—not a center of digital innovation. The compute stays in Loudoun, but the value it enables is created in places like Seattle, San Francisco, or New York.

A similar disconnect is emerging in Malaysia. While the government is betting that data center investment will turn the country—particularly Johor—into a regional digital innovation hub, the early signs suggest otherwise. Most of the data center capacity being built isn’t for Malaysian users. Through a sprawling network of submarine cables, these facilities primarily serve customers in East Asia, the U.S., and Europe.4

Upstream linkages

The picture upstream isn’t much better. Data centers are built with some of the world’s most advanced components: semiconductors, high-speed networking systems, precision cooling technologies, and specialized power equipment. These inputs are typically sourced through global supply chains dominated by firms based in the U.S., Taiwan, South Korea, and a handful of other high-tech economies. While Malaysia is expanding its role in the semiconductor value chain—particularly in assembly, testing, and packaging—these activities remain at the lower end of the value spectrum. More importantly, there’s no guarantee that foreign-controlled data centers will source components from domestic firms, especially when major hyperscalers already have established relationships with global suppliers.

Countries like Malaysia also tend to lack a strong domestic base for manufacturing many of the key upstream components that data centers rely on—such as advanced networking equipment, power distribution systems, and cooling technologies. In regions like Johor, the chances of breaking into these upstream value chains or achieving meaningful industrial upgrading are slim. The inputs are highly complex, local technological capabilities remain limited, and global suppliers are deeply entrenched. As a result, Malaysia faces the risk of becoming a host for digital infrastructure without capturing the broader economic benefits that come from deeper integration into the production ecosystem.

Potential positive infrastructure effects

There is, however, one partial exception: infrastructure. Data centers consume enormous amounts of electricity and water, placing strain on existing infrastructure. In response, host governments may be compelled to expand grid capacity or invest in renewable energy. In Malaysia, for instance, "the government is allocating 421 billion ringgit for various initiatives supporting Malaysia’s energy transition, including the National Energy Transition Facilitation Fund (300 million ringgit in fiscal year 2025) and Green Technology Financing Scheme (1 billion ringgit through 2026)" according to Grace Shao and Steven Lu.

In this respect, data centers may resemble manufacturing more than services. While they don’t create deep linkages or spillovers, they do exert political pressure on states to invest in infrastructure. Their massive needs for energy and water can drive investment in utilities, grid expansion, and potentially even renewable energy.

In the short term, however, the costs of rapid data center expansion are already being felt—often by local communities. In places like Malaysia, where energy and water infrastructure has not yet caught up to the demands of hyperscale facilities, it is residents who bear the burden. In Johor, where data center development is advancing most rapidly, locals have reported more frequent power outages and water disruptions. According to Rest of World, Malaysia’s national water regulator has warned that the country could face widespread water shortages within the next five years due to aging infrastructure and climate change—even without the added strain of data centers.

New infrastructure colonialism

Data centers provide the backbone of the digital economy, but the value that rides on top of that backbone—software, services, platforms—is often created elsewhere. That asymmetry points to a deeper problem. Rather than leapfrogging into a high-tech future, countries like Malaysia risk falling into a new kind of dependency. Instead of exporting cheap labor, they now export compute power, made possible by cheap land, water, and electricity. That compute power is then used by firms in the Global North to train models, run cloud services, and generate profits—far from where the infrastructure resides. The result is a digital version of an old story: the periphery provides raw inputs, while the core captures the value.

These dynamics aren’t limited to developing countries. In the United States, data centers are often concentrated in rural or resource-rich regions—areas with cheap energy, open land, and permissive zoning laws. Yet even in these contexts, local economic spillovers are limited. Facilities are highly automated, long-term employment is minimal, and neighboring communities rarely see the kind of broader development gains that were promised.

One potential bright spot for developing countries is tax revenue. If properly regulated, data centers can generate substantial revenue for local governments. In 2022, Loudoun County in the Virginia brought in over $600 million in property taxes from data centers which provided funding for schools, services, and infrastructure, all without raising residential taxes. For regions with strong public institutions and fiscal discipline, this could be a way to extract developmental value from otherwise footloose capital.

But that’s a big if. Tech giants often demand tax breaks, pit jurisdictions (both at the regional and national level) against one another, and externalize costs while privatizing gains. Without careful policy, the promise of long-term development can dissolve into a short-term land-and-energy grab. And in the meantime, its the local residents that will risk facing the short-term consequences.

Lewis, W. Arthur. 1954. “Economic Development with Unlimited Supplies of Labour.” The Manchester School 22(2): 139–91

Rodrik, Dani. 2013. “Unconditional Convergence in Manufacturing*.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 128(1): 165–204.

Hirschman, Albert O. 1958. The Strategy of Economic Development. 17. print. New Haven: Yale University Press

See more here: https://apnews.com/article/malaysia-johor-data-centers-energy-electricity-power-cfb087f755d3e203a347463af229e88d

I can tell you from an Irish context the short answer is No. They have spread like a rash over the landscape (loads around Dublin). They employ very few, suck the grid like a vampire and sprawl across valuable agricultural land. Meta has a 259 acre site near Dublin and pays into a community fund of 🥁 200,000 euros. Yep, the company that earns billions tosses a minuscule amount to the local community. So No, Datacentres Are Not Good.